If humans and robots collaborate, what will it mean for our wetlands?

By Samurdhi Ranasinghe, Senior Communications Officer, IWMI

Wetlands are among the planet’s most threatened ecosystems, disappearing at a rate three times faster than rainforests. In Sri Lanka, eclipsed by the hustle and bustle of the capital city of Colombo, a large and interconnected system of natural wetlands — known as the Colombo Wetland Complex — helps city dwellers thrive, survive, and fight the climate crisis. Yet, despite the many benefits the Colombo wetlands provide, they continue to be degraded with each passing day. Thoughtlessly polluted and often dismissed as marshy land or dumpsites, not many people are aware of the value of wetlands. But this wetland complex not only harbors unique and rich biodiversity — it also provides a variety of ecosystem services for urban inhabitants and functions a giant sponge, absorbing and storing excess rainfall and reducing floods.

Despite increased efforts being pooled into the restoration and protection of the Colombo wetlands, government initiatives can be strengthened by greater community engagement and enhanced wetland monitoring. To that end, the IWMI-led Darwin project has been working with partners and stakeholders to align community-led wetland management with the government conservation efforts.

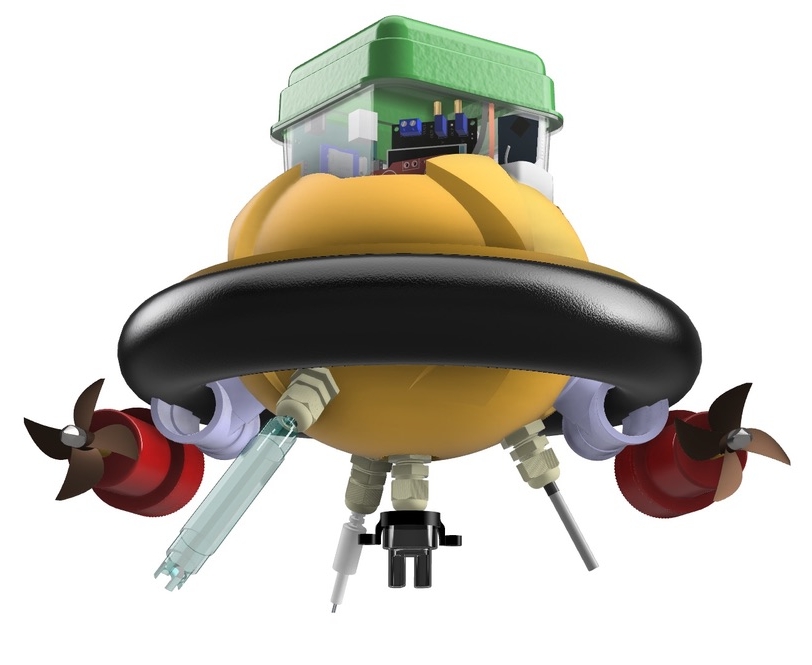

One of the project’s most recent innovations has been the development of a low-cost, easy-to-build robotic device that people can use to monitor wetland health. As one component of the Increasing the resilience of biodiversity and livelihoods in Colombo’s wetlands project, funded by The UK Darwin Initiative, IWMI and project partners have supported the creation of an unmanned surface vehicle (USV) that can be used to drive around the wetlands and collect real-time information on water quality. The device is designed to be built by citizen scientists using affordable, easily accessible materials.

The value of Colombo’s vanishing wetlands

Wetlands are essential to the well-being of the people of Colombo, particularly the urban poor. “Sixty percent of households directly benefit from wetland livelihoods and products, such as fish and rice,” says Dr. Priyanie Amerasinghe, Project Coordinator and Emeritus Scientist with IWMI. “On the other hand, a majority of the city population indirectly benefit from flood protection, climate cooling, air purification, and pest regulation.”

Since the 1980s, as much as 60 percent of the Colombo wetland area has been destroyed. Even today, a loss of 1.2 percent is recorded each year because of infilling and indiscriminate dumping of solid waste. Water quality is considered poor or very poor in about two-thirds of the wetlands. Untreated domestic waste is the main source of water pollution threatening the health of the flora and fauna around these wetlands. Meanwhile, routine dredging only adds to the damage to ecological health. “Unless we reverse this trend of wetland loss, the wetland area will decline by one-third over the next two decades,” says Dr. Priyanie. For that reason, the Darwin project aims to empower citizens to care for the Colombo wetlands while boosting direct and indirect benefits for households in order to help improve quality of life.

Diving deep into wetland health with the help of robotics

A key aspect of the project involves the promotion of a community-driven approach for the wise use of wetlands. And ‘Float’ — the simple and easy-to-make citizen science robotic device — has risen to the challenge of helping communities around the wetlands more accurately and efficiently monitor the water quality of wetlands.

Float is a concept introduced by Luisa Charles, a double master’s Design Engineering student at Imperial College London and the Royal College of Art. The device has been developed through community workshops and basic robotics skill-sharing. “Getting data from places that a human can’t go — that is the concept I brought to this project,” says Luisa. “Float in Sri Lanka is something you can build by yourself, with basic and readily available material, to collect real-time water quality data. I have invented a prototype that works, but I expect the design to evolve. The code is open-source, meaning it will be freely available on the Internet for anyone to use. And people are also free to make it into something better,” she adds.

Perfecting Float in Sri Lanka required Luisa to work closely with local engineering students, wetland communities, and other partner organizations in Sri Lanka. During her recent visit to Sri Lanka, she worked with PhD students from the University of Moratuwa’s Department of Electrical Engineering to devise the electrical setup of Float with their engineering support. She also conducted workshops to gain design insights directly from the people who the technology is meant to be used by, helping her make Float more suitable for users and the environment.

The initial field tests for Float have now been completed. While her design for Float is available in diverse models, for 3D printing or fiber glass, the basic USV model can be made from easily accessible resources. For example, the materials needed to build a basic Float device include common items like a pressure cooker gasket or a three-wheeler’s (tuk tuk’s) inner tire tube. Once fully assembled, the device can be operated manually to cruise through the wetlands. The data is then stored on a memory card and can be downloaded as a separate file — a CSV file in this case — onto a computer.

As a next step, Luisa has been working closely with a local non-profit organization, Emotional Intelligence and Life Skills Training Team, to develop a mobile application that people can easily download and use to feed in the data collected by Float. In addition to that data, users would also be able to add other relevant observations to this mobile application, such as the color of the water, signs of dredging or drainage, and so on.

Luisa’s work on this interactive design focuses on looking at human psychology and exploring how people behave when designing a device. “It’s about looking at whether people actually use your design once it’s in their hands, and what’s going to motivate them to keep using it, and which type of functions would make them continue to use it,” she explains. “And in the end, it’s about being able to design a device so that when someone picks it up, they don’t need a manual to use. They would rather intuitively know how to use it.”

Luisa has an intriguing professional background as a trainee working on Hollywood movie sets, and her accomplishments range from designing action vehicles on Star Wars (Ep. 9) to designing props on Jurassic World and working on special effects for the recent Marvel movie, Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness. She emphasizes that she finds it equally exciting to work on interactive designs that bring attention to climate change or environmental issues. Float is her final year major project with the Imperial College Robot Intelligence Lab. She is partnering with IWMI and Cobra Collective on this Darwin project on Colombo’s Wetlands, with facilitation by the University of Moratuwa.

“A prototype has been developed and the concept proved. The next step is to further refine the design and work with communities and students to ensure applicability,” says Dr. Matthew McCartney, Project Leader and Research Group Leader of Sustainable Water Infrastructure and Ecosystems at IWMI. “This high-tech but accessible tool allows researchers and communities to monitor water quality in their wetland, contributing to better understanding of trends and hence wetland health.”