New estimates provide a starting point for more strategic thinking about how to manage and protect vital freshwater sources

By Matthew McCartney, Research Group Leader – Sustainable Water Infrastructure and Ecosystems, IWMI

The need for freshwater – for drinking, washing, irrigation, industry, and energy – grows as societies develop. Because water availability varies in both time and space, storage of water in natural stores (i.e., glaciers, permafrost, groundwater, lakes, wetlands, and soils) and man-made stores (i.e., small and large reservoirs and paddy fields) is a prerequisite for socioeconomic development. Stored water is also vital for ecosystems and biodiversity.

The importance of freshwater, and hence water storage, will only increase as populations grow and the impacts of climate change become more pronounced. This is recognized in many national adaptation strategies, where water storage is identified as an adaptation mechanism.

Mainly because of the complex distribution over extensive areas as well as difficulties in monitoring, the total amounts of water in terrestrial stores and the rates at which they are changing have remained largely unknown. But recent advances in Earth observation and computer modeling enable more accurate estimates of different stores and trends in water storage.

An overview of these estimates has been published in an IWMI Working Paper led by Matthew McCartney, Research Group Leader – Sustainable Water Infrastructure and Ecosystems. “Although still relatively crude, the estimates are a useful starting point for more strategic thinking about how to manage and protect the Earth’s freshwater stores,” he says.

Estimating total water storage

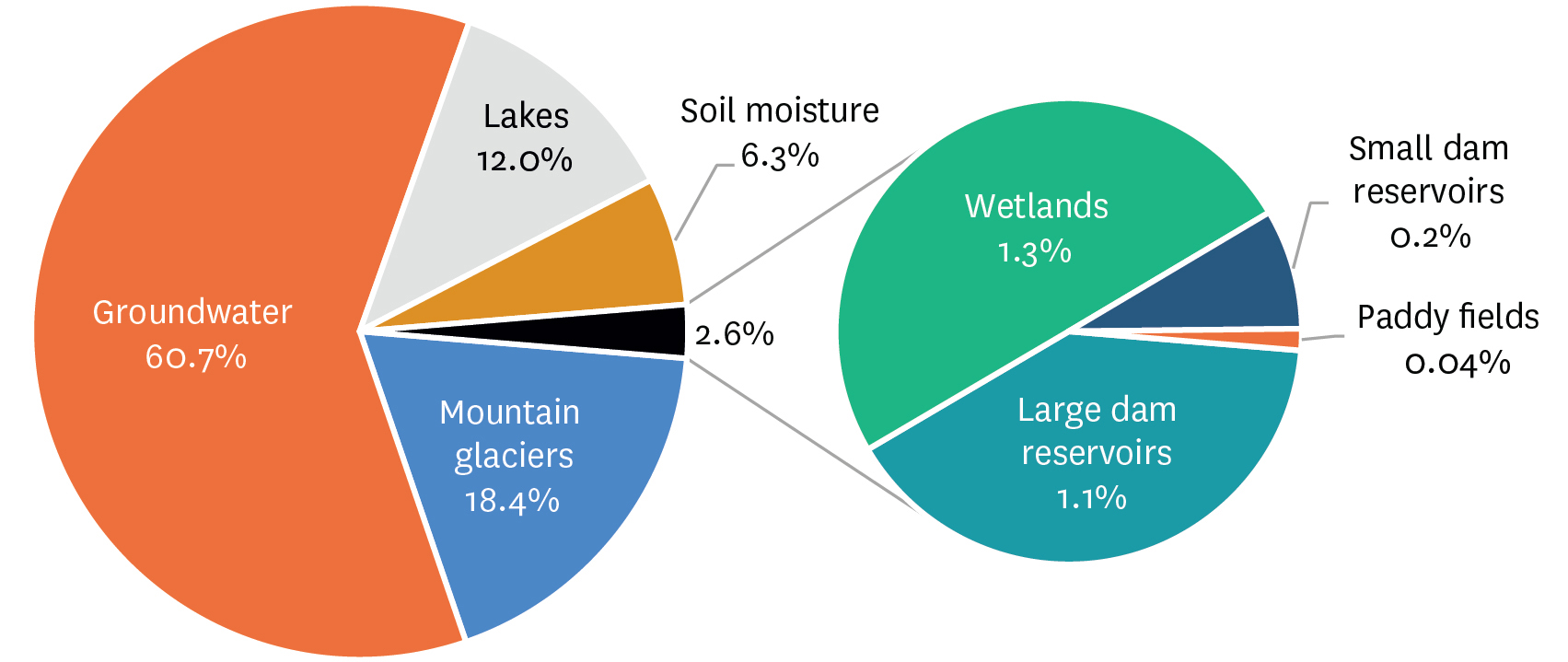

The authors considered the main terrestrial water stores, their contribution to total volume stored, and the trend in each type of water storage between 1971 and 2020.

“Inventories of most forms of water storage, even man-made stores, are not systematically produced at national or regional levels. So, we reported estimates from a wide variety of sources that had used a range of estimation methods, including computer modeling,” McCartney explains.

Based on these sources, total water storage in ice caps, glaciers, and other terrestrial water stores is estimated to be approximately 53 million billion cubic meters (Bm3), of which approximately 42 million Bm3 is freshwater. Of total water storage, 99.5% is in ice and groundwater. By comparison, man-made storage — though essential for people’s wellbeing — is insignificant, comprising less than 0.02% of total global water storage.

Water for human use

From a human water security perspective, not all forms of water storage are equal. A range of biophysical and socioeconomic factors determine whether water can be withdrawn from storage for human activities. The authors coined the term ‘operational’ water storage for storage from which freshwater can be withdrawn sustainably for direct human use.

By separating total water storage into its component parts, the authors were able to estimate global operational freshwater storage. This amounts to approximately 850,000 Bm3 or 2% of total water storage.

What the numbers tell us

Given the nature of the data available, much uncertainty remains. Overall, however, the assessment indicates that due to melting glaciers, decades of degradation of lakes, wetlands, and soil, sedimentation of man-made reservoirs, and overabstraction of groundwater, global terrestrial water storage reduced by approximately 27,000 Bm3 between 1971 and 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Estimate of operational water storage and change for the period 1971-2020.

This change is insignificant in terms of the total storage volume at the global scale. However, it is much more significant in relation to operational freshwater storage. Conservatively, the authors estimate that there has been a decrease of more than 3% in operational freshwater storage since 1971. Declining operational water storage is a major contributor to local and regional water crises that ultimately threaten people and ecosystems worldwide. In many places, both natural and man-made water storage are declining simultaneously, exacerbating water stress.

Adapting to a new reality

“The demands of growing and increasingly thirsty societies with rapidly changing consumption patterns for food, mobility, and energy are putting pressure on already strained water resources. Additionally, we are likely to see greater frequency and severity of extreme weather events as a result of climate change,” says McCartney.

Water use and management practices must adapt to a new reality, he concludes. “In the future, water storage will become more important for supporting adaptation and the resilience of societies. Storage options must be flexible to deal with uncertainty. More efforts are needed to protect and restore existing storage. It is vital that natural water stores are fully integrated, alongside man-made water stores, in water resources planning and management.”