By Solomie Gebrezgabher and Tania Perera

There were about 4.9 million refugees and 12 million internally displaced people in the eastern subregion of the African continent at the end of 2021. These populations are often hosted in regions characterized by fragile and degraded dryland zones. In these landscapes, competition for resources like water, firewood and arable land often leads to social tensions between refugee settlements and the local host communities. Climate change exacerbates the increasing pressure on limited resources as refugee populations increase due to civil and political unrest in many countries.

Harnessing greywater for micro-irrigation

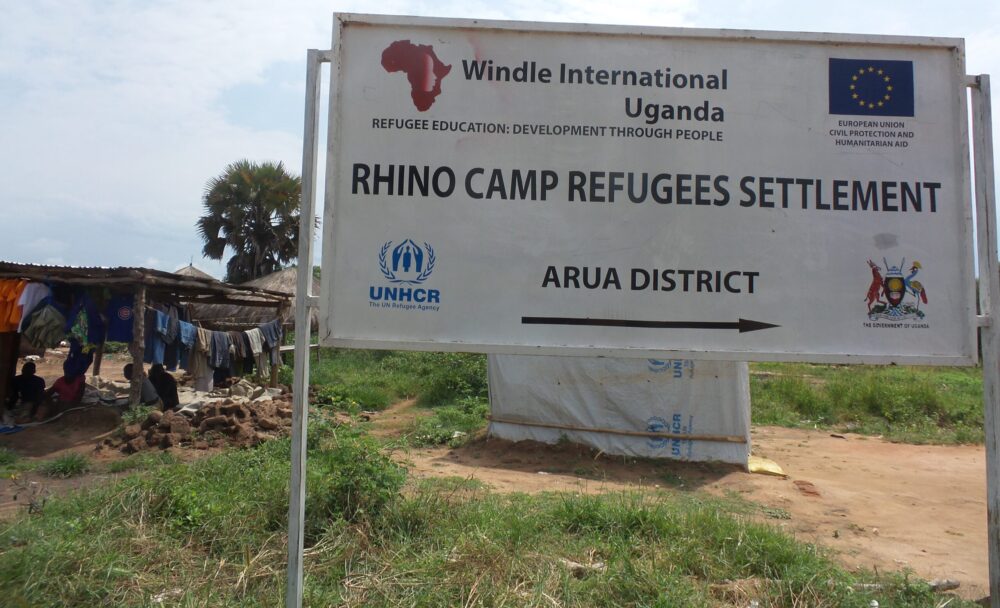

In these landscapes where water is scarce, there is an opportunity to safely reuse greywater and other organic wastes for home gardening. The Resource recovery and reuse (RRR) in refugee settlements in Africa project has put nature-based circular bioeconomy principles into action in six refugee camps and settlements and their surrounding host communities in Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda. Circular bioeconomy approaches can be used to improve the safe collection and reuse of greywater and other organic waste, providing essential inputs that enhance food and nutritional security in areas hosting refugees.

This means refugee and host community households are complementing a cereal-based diet by cultivating other nutrition-rich produce in their home gardens. They are using domestic greywater—household wastewater generated from kitchen, bath and laundry that does not contain contaminants (as from toilets)—to irrigate these gardens. They are also reusing organic waste such as kitchen waste, garden waste and charcoal dust to produce compost and briquettes. The composted material is used in the home gardens and the briquettes for cooking. This is the biocycle in action.

Masabimana Devot is a refugee displaced to the Kalobeyei settlement in Kenya. Devot went a step further, directing runoff from the area around the community tap into a hole she had dug which she then collected and used to water her vegetable garden. “I also collect animal manure, mix it with other organic residue, including carbon and ash, and use it as a fertilizer,” explained Devot. The use of greywater means vegetable gardens can be irrigated and maintained throughout the year, providing an important source of additional nutrients.

Bouquets for briquettes

Dominica Maliko is part of the host-community population at Imvepi in Uganda. “I like using briquettes because they burn longer and have no smoke. They are good for cooking multiple meals. I even sell some at my shop where I make some income from it,” she said. The use of briquettes has maximized the efficiency of cooking processes with less fuel and time required to cook the same amount of beans than previously. There is less air pollution when the stove is built and used indoors while the dual-purpose stove allows women to use both briquettes and firewood. The use of briquettes has the potential to reduce deforestation and land degradation, if employed at scale. Briquettes are also gendered in their impact because their use means women and children spend less time and energy searching for and collecting firewood for cooking.

The biocycle has had yielded additional benefits such as income generation and fostering entrepreneurship. Rebecca Nyakuany used the income from the sale of surplus home-grown vegetables to open a shop in Kakuma where she sells snacks and githeri, a dish combining maize and beans. An additional source of income has helped women like Rebecca to make purchases including books for her children.

So far, the project, in partnership with the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry, the Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT and the Danish Refugee Council, has directly reached over 3,600 households and indirectly reached over 200,000 individuals from both refugee and host communities in Kenya and Uganda.

Impacting lives, safety and well-being

Gender expert Ruth Mendum explained that the gender dynamics of refugees and internal displacement means there are many families led by women in the camps taking care of not just their own children but children from other families or from their villages of origin. It is a lot of work, and it takes a lot of time as these women are operating in circumstances where food is hard to find, and firewood is the way most people cook their meals.

It is in this context that the project introduced home gardens which provide not just more food but more nutritious food, as well as briquette-making technology as a better, safer, and more sustainable way to cook that food. The use of domestic greywater for irrigation in a water scarce region improves food security with knock-on environmental, economic and social impacts.