By Maha Al-Zu’bi, Oyture Anarbekov & Zafar Gafurov

In Central Asia (CA), water resources are mostly surface transboundary in nature, mostly generated in the mountains of upstream countries Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan and flow into the two main rivers Syr Darya and Amu Darya to downstream countries Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Water is critically important to the Central Asia region’s socio-economy, people, environment and security. In the upstream countries – Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, water is important for energy production – hydropower energy covers more than 90 percent of the total electricity needs and is also an export commodity. In the downstream countries -Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, water is essential for agriculture production. The competing demands of hydropower generation in upstream countries and of agriculture production in downstream countries fuel significant regional tensions in the region, putting water at the heart of regional security and stability. Extreme climate, such as drought, heatwaves and rainstorms, will have a 10% negative impact on agricultural production and the ecological environment.

CA countries are typically agricultural producers, planting many water-intensive crops, such as rice and cotton. Irrigation consumes a large amount of surface water. This, combined with inefficient water utilization, leads to severe river and groundwater depletion. Therefore, water-related problems in CA are prominent with water resource shortages a crucial factor in restricting socio-economic development. For instance, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan belong to the “severe water stress” category, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan both exhibit “moderate water stress” and Tajikistan is classified as “high water stress”. Therefore, water scarcity will cause not only disputes and conflicts between countries, but also between supply and demand in urban and rural areas within each country.

The need for cross-sectoral and interstate cooperation

The CA region has sufficient resources to meet collective demands for water, energy, food and environmental security but there is a significant need for interstate cooperation in order to negotiate trade-offs, coordinated actions and cooperation between the countries to address challenges related to sustainable use of resources. Transboundary water cooperation is the key for sustaining peace, stability and prosperity in the region. Making appropriate decisions for the allocation of water for communities, the environment and key economic sectors, such as agriculture and energy, is increasingly challenging due to socioeconomic factors and population growth as well as climate-induced changes in hydrological regimes in Central Asia’s main transboundary river basins. The IPCC special report on oceans and the cryosphere in a changing climate (2019) highlights the combination of water governance and climate risks as potential reasons for tension over scarce water resources within and across borders, notably competing demands between hydropower and irrigation, in transboundary glacier- and snow-fed river basins in Central Asia. The report notes that “within the transnational Syr Darya and Amu Darya basins in Central Asia, competition for water between multiple uses, exacerbated by reductions in flow later in this century, may hamper future coordination.” Research results revealed that the situation will worsen if no internal and cross-boundary effective actions are taken.

Transboundary water resource management is complex and multidimensional, entailing several powers, interests and collaborative relationships across multiple political jurisdictions; across geographic landforms and administrative boundaries; across social, economic, environmental and ethnic cultures, ideas and perspectives; across sectors and disciplines. Even where joint institutions exist, the growing pressures on water resources––coupled with the impacts of climate change––amplify the challenges in implementing existing agreements and achieving progress in transboundary water cooperation, thereby calling for strengthened governance frameworks, policy dialogues, and joint mechanisms to build and strengthen ties and relationships to address the transboundary challenges and find solutions for all nations.

Water Efficient Allocation in a Central Asian Transboundary River Basin

In response to these challenges, the International Water Management Institute is working with Water Efficient Allocation in a Central Asian Transboundary River Basin (WE-ACT)-an innovative European Commission Horizon Europe project- to help the various stakeholders in the region -particularly in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan- balance their shared water needs and water usage from the Syr Darya River.

Due to the heterogeneity of the physical, political, environmental and socio-economic contexts between Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, there is no one solution fits all nor practice or method for managing transboundary water-related issues. Through risk-aware planning and management, supported by data and technology, WE-ACT assigns value to water resources and empowers stakeholders to allocate scarce water resources effectively. It proposes establishing a climate-sensitive Decision Support System (DSS) for water allocation in two sub-catchments of a transboundary river basin in Central Asia, namely the Naryn and Kara Darya catchments of the Syr Darya River Basin (covering parts of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan) up to the boundaries of Tajikistan in Ferghana Valley.

Water-related disaster risk management involves a variety of disciplines, institutions and stakeholders that are active at different levels in time (sequential interventions) but also at different scales (transboundary actors like basin-wide institutions, national actors including line ministries/authorities and local actors such as governorates, municipalities, local communities). Therefore, transboundary cooperation is crucial to address the complexity and scale of the challenges faced in managing transboundary basins. Achieving successful transboundary water management will require coordination within and across sectors and actors, coherent policies, and integrated planning.

Stakeholders’ analysis and engagement in water transboundary context

The stakeholders’ engagement and analysis within a transboundary water context is complex and highly context specific process considering upstream-downstream demands and the pursuit of sovereign “power” and “interest” as key factors usually leading to fragmented water resource management. For instant, in the Naryn and Kara Darya catchments, Kyrgyzstan is considered ‘energy-poor but water-rich,’ whereas Uzbekistan is ‘energy-rich but water-poor’ as a downstream country. Upstream, Kyrgyz Republic covers a substantial portion of the transboundary basin in both catchments, offering abundant blue water from surface and glacier sources, along with large hydropower plants. Downstream, Uzbekistan heavily relies on upstream water resources for irrigation, given its relatively poor internal water resources.

Stakeholder collaboration under these conditions requires common interest from which each country can benefit and join decision needs to be designed using a framework of shared vision, planning and tailored to the specific purposes and issues of the stakeholders. When a transboundary river basin is viewed as a system, it can have various points for initiating change, but finding “leverage points” (i.e., points where a small change can lead to a large change in the system’s behavior) requires a good understanding of system’s goals, elements and links. In this respect, viewing stakeholders as links around the common/connecting element of water, can provide an opportunity to identify key stakeholders in the system who can initiate the largest change in the system’s water demand and water use behavior.

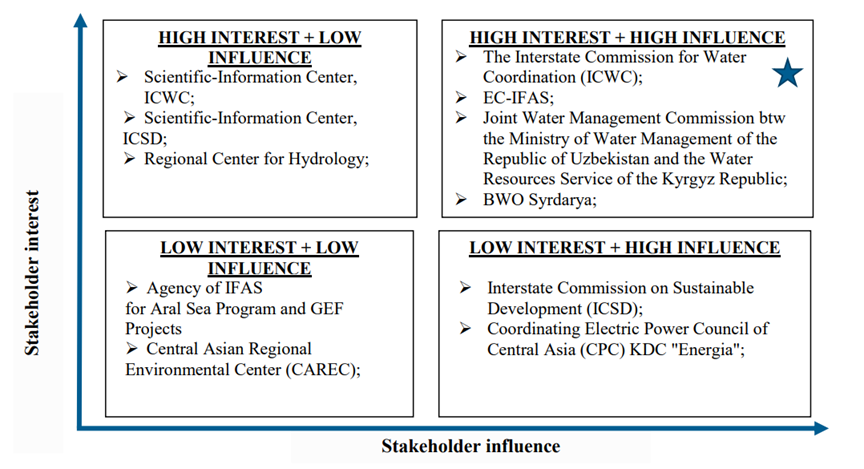

IWMI in 2023 led the engagement and stakeholders’ consultation process over eleven months covering stakeholders across different sectors in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, fully mobilizing IWMI’s network of local, national, and regional partners and institutes. The focus was to identify, analyze and group stakeholders with similar attributes (e.g. power, interest, influence, gender, expectations, roles/positions, backgrounds, sector, network) in order to: (a) understand variations/similarities in their needs, demands and information sources; (b) identify and explore different entry points to achieve the desired change; c) identify stakeholders’ power, influence and interests over transboundary water allocations and d) illustrate roles and responsibilities of the key stakeholders in the context of transboundary water allocation.

Drawing on IWMI’s vast experience in CA, the consultation process identified both formal and informal functions that come with different roles and positions and answered pressing questions, like who needs data exchange, when, and what kind of functions do they expect an effective tool to provide. With the help from the regional partners, the team mapped and analyzed the existing governance and management structure involved in transboundary water allocation, roles, positions, gender distribution and responsibilities that come with them.

The stakeholder analysis has provided valuable information on the institutional context at different scales, from local to transboundary levels, as well as the governmental and non-governmental organizations in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan involved in water governance, management, irrigation, and drainage system operation and maintenance. The data collected will aid in conceptualizing management initiatives to overcome transboundary water management-related bottlenecks specifically by advancing the benefits of a decision support system in transboundary water allocation. Studies show that transboundary water cooperation promotes increased energy and food production, enhanced resilience to disasters and regional economic integration.

Key Principles for stakeholders’ engagement within Naryn and Kara Darya River Basins

The water challenges in the Naryn and Kara Darya Basins underscore the critical need for collaborative and effective stakeholder engagement strategies. The first step in the engagement process was identifying who they are and determining what motivates them. It was crucial to first gather more in-depth information about the stakeholders, especially seeking to understand the individuals we will be working with and relying on throughout the various phases of the engagement process. Next, was establishing local and regional communication channels to share information with stakeholders at all levels. Regular communication was essential to ensure the satisfaction of high interest, high influence stakeholders. Consult early and often was another important principle particularly in the early stages was essential to ensure that requirements were agreed upon, and a delivery solution acceptable to the majority of stakeholders was negotiated. Addressing the water challenges in the Naryn and Kara Darya Basins requires a comprehensive, cooperative, and participatory approach. Implementing these principles in stakeholder engagement will contribute to addressing historical issues, fostering regional collaboration, and ensuring the sustainable and equitable use of water resources. Bilateral transboundary water allocation is a process of joint, interactive planning, joint decision-making, implementation and evaluation, involving two transboundary states stakeholders.

We-ACT is funded by the European Union. However, any views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency (REA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.