P. Stapleton, C. Patacsil

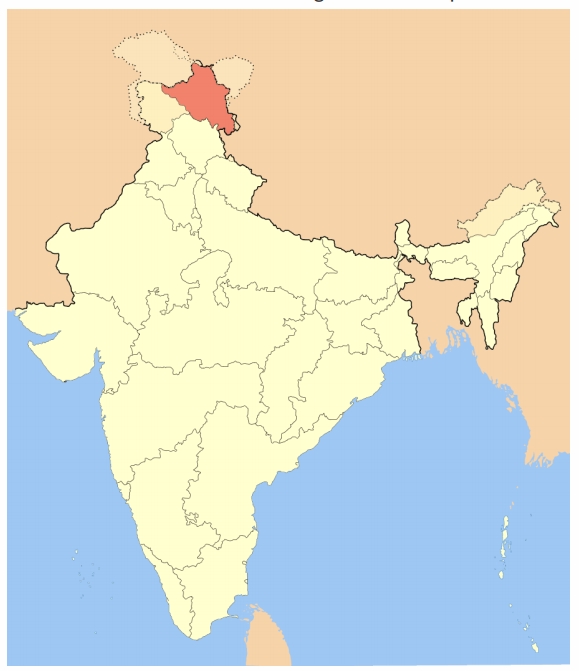

Innovative water-harvesting techniques – the ancient practice of glacier grafting and the new technique of building ice stupas – are helping the farming communities of Ladakh in the far north of India to grow more crops and increase their resilience to climate change.

If we are to believe local legends, when Genghis Khan and his marauding Mongols reached what is now northern Pakistan, the local people grew glaciers across his path to keep the army out. Whether this story is true or not, the art of ‘glacier grafting’ has been practiced for centuries in the mountains of Hindu Kush and Karakoram ranges as a way of storing water in the winter for slow release during the spring growing season. However, an even more startling idea is being tested in the area, where spring water is sprayed into the air to freeze and form spectacular conical glaciers or ‘ice stupas’, which in this case melt and irrigate newly planted trees.

Both these innovations are described in a report published recently by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI)–Tata Water Policy Research Program (ITP) and authored by Dr. F. A. Shaheen, a scientist in the State Agricultural University of Kashmir, India.

In Ladakh, all of the cultivatable land depends on irrigation from glacial melt water. Water is scarce during the sowing season of April–May, so Chewang Norphel, a retired local civil engineer of Leh, decided to revive the ancient tradition of glacier grafting. Since 1987, he has overseen the creation of 10 artificial glaciers. The local communities dig water channels and construct small dams high up on a valley slope, between 3,350 and 4,267 m above sea level. During the winter, water from the main stream is diverted into this complex and runs downhill, and is stopped by a series of dry stone walls built along the lower contours. There it freezes and a huge reserve of ice accumulates on the mountain slope over 3–4 months. The glacier located closest to the village melts first and provides irrigation at the crucial sowing time in April. As the temperature rises, the next glacier melts. By the time all the artificial glaciers have disappeared, the high altitude snow starts melting.

“The local farmers are very happy with the results,” said Dr. Shaheen. “Over 2,000 families have increased their income three or four times by growing crops with a better cash return. They are also earning money by raising livestock on the new pastures they can create.”

The glaciers have other benefits. They slow down water flow and allow groundwater recharge. People do not spend so much time accessing water. There are fewer disputes over water and there is more employment in the villages, so fewer people are migrating.

The Ice Stupa Project was conceived by Sonam Wangchuk, a local mechanical engineer and founder of the Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL). After earlier testing, SECMOL collaborated with the Phyang Monastry to create a full-scale structure in the winter of 2014–15 in Phyang village in Ladakh. Funds were raised by crowd funding and villagers donated their labor.

High up in the valley, but not so high as artificial glaciers, pipes are laid to bring water down to where it is needed. With an altitude drop of about 65 m, the water sprays up vertically and freezes almost immediately, forming ice cones 30–50 m high. Five-thousand willow and poplar saplings were planted in the desert below the glacial structure and irrigated as the stupa melted, which lasted until mid-May. With good care, the trees will reach a marketable size in just 6 to 7 years, and they are particularly valuable as no other wood is available locally.

The project plans to build a cascade of 80–90 ice stupas to store one billion liters of water, enough to cover the entire Phyang desert (600 ha) with a plantation of 2 million trees. Apart from the economic and employment benefits, this will transform the whole agrarian structure of the cold, arid and barren desert, boosting the livelihoods of the local people and sequestering carbon. In recognition of the project, Sonam Wangchuk was a 2016 Rolex Awards for Enterprise laureate.

These high-altitude, water-conservation techniques could be replicated in similar regions such as the Himachal Pradesh in India, the Hindu Kush in the Himalayas of Pakistan and Afghanistan, and in some central Asian countries like Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. “Researchers and development agencies need to take a serious look at restoring and developing the art of glacier grafting to address the water problems in these regions,” said Dr. Shaheen.

Read the report:

Shaheen, F.A. 2016. The art of glacier grafting: Innovative water harvesting techniques in Ladakh. IWMI-Tata Water Policy Research Highlight 8. 8p.

Some of the research underlying this IWMI-Tata Water Policy Research Highlight was funded with support from the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE).

Photo courtesy Shyam G Menon: https://shyamgopan.wordpress.com/2015/08/28/imagining-a-university-for-ladakh/