Is it surprising that in the aftermath of the financial crisis, in a global economy growing on credit, physical assets like land and crops are gaining value?

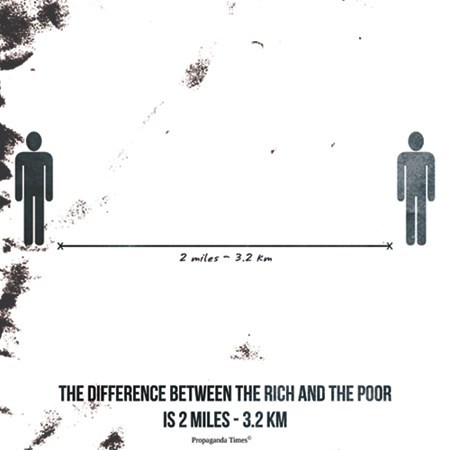

Inequality is back. Not the fact of it, of course. The startling and frankly criminal scale of income disparities between citizens in the global economy have been growing larger for more than a generation now. But, for most of that time, the word itself was a no-no among politicians and economists. As if, by not speaking it, they could make it go away.

The orthodoxy was the view of the Nobel prize-winning Chicago economist Robert Lucas, who wrote in 2003 that to discuss inequality was “poisonous”. Better to talk about banishing poverty since the consensus held that unleashing market forces could generate more for everyone. Inequality might be the price we had to pay for that.

Subsistence farmers, pastoralists and forest dwellers alike should join the global economy ASAP, maximising production of cash crops, driving their animals to market and seeking out transnationals to buy their forest harvests. Or, more likely, they should sell up to the local land grabber and head for the city to make their fortune.

But those certainties are evaporating. Wherever the economic pie ceases to grow, the reality of stubborn structural inequality is laid bare.

Last autumn, The Economist, the house journal of capitalism, ran a special supplement on inequality, declaring that a topic it had rarely raised before was now “one of the biggest social, economic and political challenges of our time.” The Gini index, which measures income inequality, has gone from pariah to pole position in economic debates.

The OECD and UNCTAD have both penned major reports on the topic in the past year or so. The World Bank claims ownership, noting how “since World Bank economist Branko Milanovic published his book The Haves and the Have-Nots in early 2011, the discussion over inequality has heated up around the globe.”

And with it we will need to reframe how we think about agriculture, about who has access to natural resources, and much else. If agribusiness doesn’t banish poverty and ensure full stomachs; if handing natural resources over to the self-proclaimed “wealth-generators” does not deliver wealth for all, then the nostrums of the past three decades fall. Maybe the locals should have a try.

Even parts of the corporate world get it. Unilever chief executive Paul Polman claims he wants to improve the lives of half a million of his smallholder suppliers of tea, tomatoes, palm oil and the rest of the company’s agricultural raw materials. He told me recently that the “end result” of ignoring inequality was that “today the richest 400 Americans have more wealth than everyone in India.”

Enter a timely I-told-you-so insight from veteran development economist, Robert Wade of the London School of Economics. A sometime employee of the World Bank – an organisation that he says “operates without memory of its own history” – he recently reminded it of the worlds of its former president from 40 years ago, Robert McNamara.

Speaking at a time when inequality was much less than today, McNamara promised in a lecture in Nairobi in 1973 to “eradicate absolute poverty by the end of the century”. He knew what his successors forgot: that inequality would not float away on a tide of rising economic activity.

“The growth of GNP is essentially an index of the welfare of the upper income groups. It is quite insensitive to what happens to the poorest 40 per cent,” McNamara said back then. “Despite a decade of unprecedented increase in the gross national product of the developing countries, the poorest segments of their population have received relatively little benefit [because] rapid growth has been accompanied by greater mal-distribution of income.”

Because the world forgot this, poverty has not been banished.

Growing inequality is a phenomenon of the rich and poor world alike. In the late 1970s, the top 1 per cent of income earners in the US took 9 per cent, a record low for the 20th century at least. Sometime around a decade ago, their share rose through 20 per cent and keeps on rising. Reaganomics didn’t deliver trickle down even in the US.

Meanwhile, among BRICS nations, income inequality has increased over the past 20 years in China, India, Russia and South Africa – in the latter case, notwithstanding the end of apartheid. It has declined in Brazil, but that country remains one of the most unequal societies on Earth, with the resulting anger sufficient to trigger the recent urban riots.

Once, inequality was seen as helping to drive economic growth. Now the IMF says that income inequality hobbles economic growth because it is inefficient. If bright kids can’t get to school because their families are too poor, then that will deprive their national economies of a primary resource at least as valuable as any high-grade metal ore. Meanwhile, the Economist embraces Ward’s critique that high income inequality feeds on itself by creating “social prejudice” against the poor that underpins both undemocratic governance and regressive tax and other policies.

UNCTAD’s report argued that “excessive concentration of income was one of the factors leading to the global crisis as it was linked to perverse incentives for the top income earners and to high indebtedness in other income groups.” The report’s author, UNCTAD’s director of globalization and development strategies Heiner Flassbeck, has since argued that there will be no recovery while "income inequalities continue to rise.”

These are interesting times. If we must live less on credit, then real assets will matter more. Physical assets like land and crops in the fields. Some realise this. It is surely no accident that the great global land rush began in 2008, in the aftermath of the financial crisis. Nor that the push to monetize nature as “natural capital” is coming to the fore, in everything from carbon offsets to payments for ecosystem services.

But it should be ever clearer that stealing from the poor to give to the rich is ultimately bad economics as well as bad ethics.

Comments

You bring up some good ideas about how income inequality hinders economic growth. There might be brilliant children who have great potential but if they can't afford to get the schooling they need to excel then of course the economy won't grow like it needs too. Thanks for the post.