Striving for a groundwater-secure future in the Limpopo

How shared resources and a community-focused water management system could be the solution to a land ravaged by climate crisis

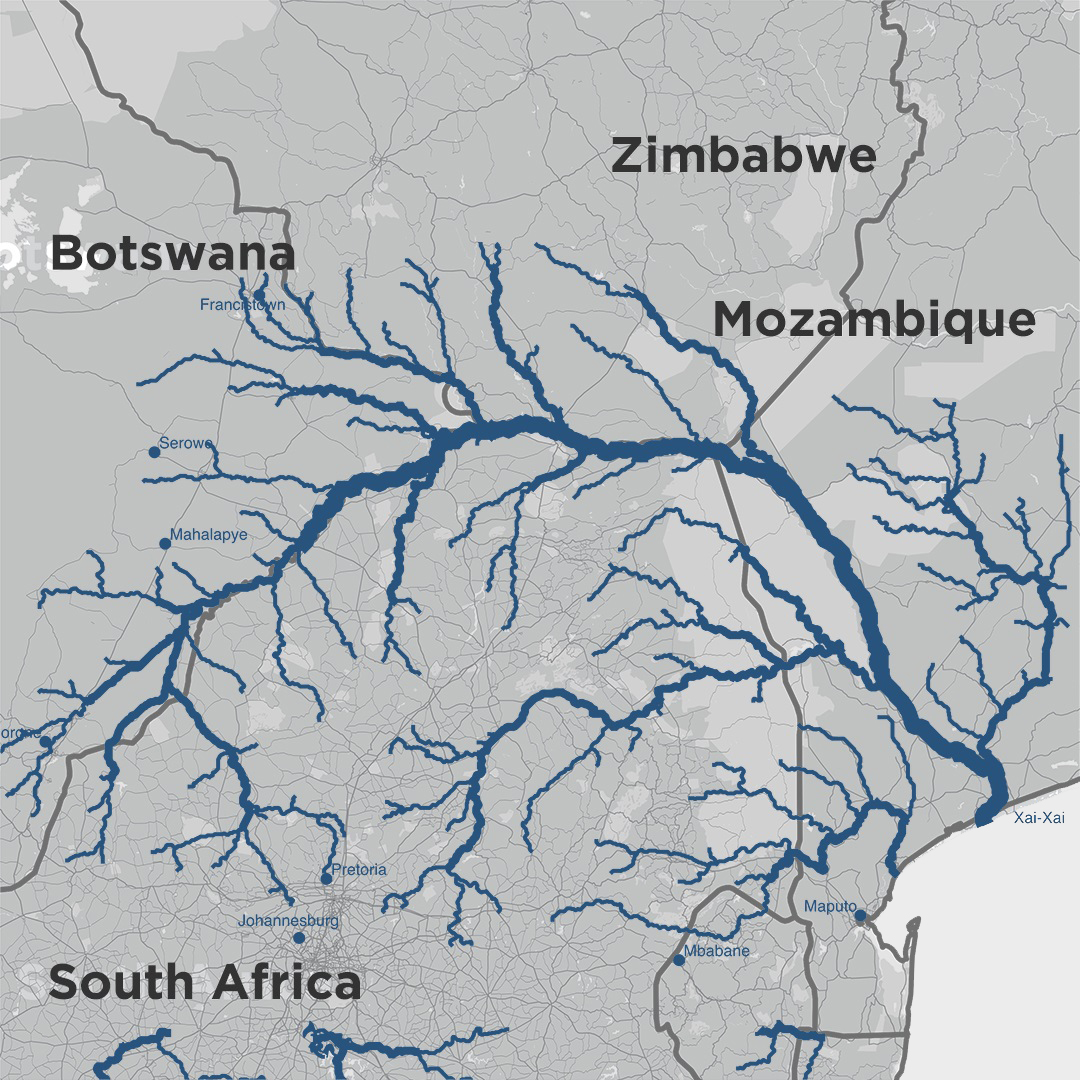

The Limpopo River Basin is the driest it has been for 35 years. It winds its way through four countries – Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. Underneath the arid, burnt-yellow landscape, are groundwater-holding aquifers. They too, are at risk of running low during droughts, but better management of the groundwater supplies could transform residents’ lives. Groundwater is the foundation of water security and climate resilience across Africa. It’s plentiful, and yet four in ten people across the continent lack access to good, clean drinking water. Just one percent of farmland is irrigated using groundwater, and drought is a serious problem for many countries.

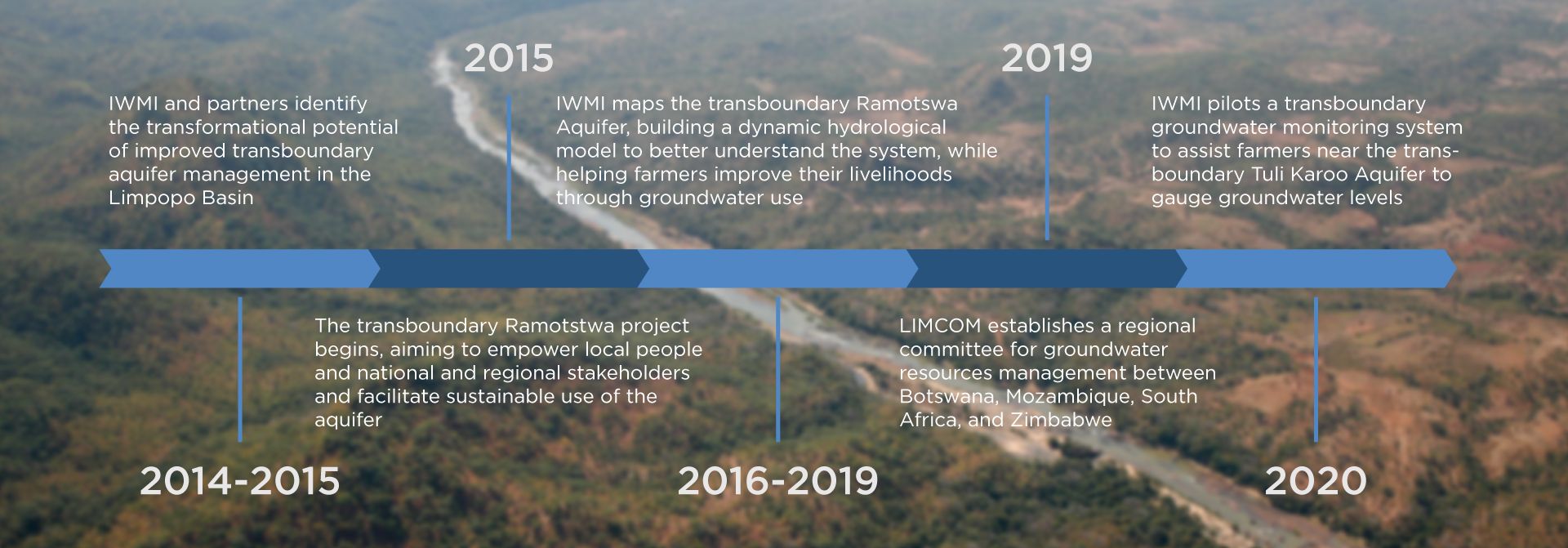

Improving sustainable access to these reserves of groundwater could be game-changing. Researchers from IWMI, with the financial support of USAID and help from national departments responsible for water and sanitation, the Limpopo Watercourse Commission (LIMCOM), the CGIAR Water Land and Ecosystems research program (WLE) and the Groundwater Solutions Initiative for Policy and Practice (GRIPP), worked hard to give local farmers and urban users the technical and theoretical tools to keep track of their groundwater reserves.

What followed, turned into one of the biggest water success stories in the region.

Groundwater is of strategic importance in the Limpopo River Basin. It is key to water security, climate resilience and prosperity — but only if continuously managed and protected and used wisely in conjunction with surface water supplies and other secondary resources, like properly treated wastewater

Karen Villholth, Principal Researcher and Project Lead, IWMI

3

potentially prolific transboundary aquifers

identified in the Limpopo River Basin

Background

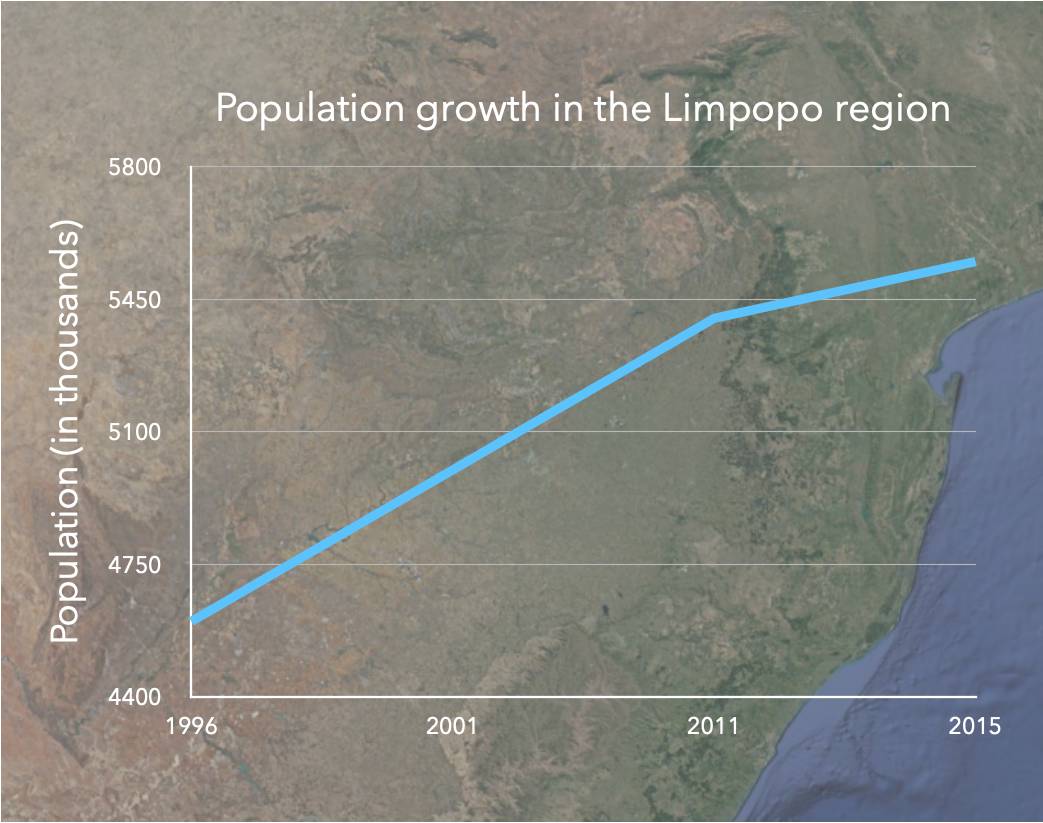

The Limpopo Basin’s population is increasing. In 2012, the population was around 18 million, and it is estimated to grow to 20 million by 2040. This population increase is putting pressure on the region’s natural resources. In addition, major cities including Johannesburg, Pretoria, and Gaborone lie upstream, which adds to the pressure on water supply, and causes scarcity and pollution downstream.

The Limpopo Basin has experienced severe droughts in the past, as boreholes and rivers dry up. Reduced rainfall led to declaring the Limpopo Province in South Africa a disaster area in 2016. Crop failure and economic hardship was widespread. It is clear that to avoid serious drought impacts again, the river basin needs to be resilient and able to absorb shocks.

Groundwater could be the answer, but it is not always easily accessible. Sometimes it doesn’t replenish quickly enough, it is deep below the ground surface, and other times, especially when aquifers are close to the sea, they might become saline. The transboundary Ramotswa Aquifer, shared between Botswana and South Africa, is ‘user-friendly’, in the sense that it provides ample groundwater when you insert boreholes, it is relatively shallow and it’s located close to where people live. Hence, the project aimed to improve people’s access to clean water from this aquifer, while also addressing farmers’ hardship in getting groundwater for their crops outside of the Ramotswa Aquifer area. IWMI is a leading partner in the RAMOTSWA project.

We sometimes go for days without bathing as we try to preserve the little water we have for drinking and cooking. It is not healthy. If it does not rain in the coming weeks, I do not think we are going to survive this time around. This drought has gone for too long now.

Mavis Chauke, resident, Limpopo Basin

The challenge

Before IWMI and their partners took on the project, there was limited knowledge around the role the Ramotswa Aquifer, and other transboundary aquifers, could play in supporting resilience in the basin. Also, it was unclear how to manage such ‘shared’ or transboundary resources, as this was never attempted before. The key aim of the project was to jointly understand the aquifer and the water challenges in the area, while identifying possible solutions, both from a technical and management perspective, so that these resources could help underpin resilience long into the future – a future with a more erratic climate.

Implementing a solution

Kicking off in 2015, the RAMOTSWA project used both innovative and traditional techniques to better understand the aquifer. Some of these included the use of ‘airborne geophysics’, computer models and scenario analysis of various solutions that could enhance the secure access to sufficient and clean groundwater from the aquifer. Fundamental data were collated with the help of local and national partners to ‘stitch’ the knowledge together across the border, which had never been done before. Data were then shared between the countries and through joint learning the issues around groundwater and its use and management were ‘unearthed’ and discussed. This led to consensus on key development challenges and priorities in terms of investments that could enhance water security in the border region.

Groundwater is critical to combat the coronavirus disease (Covid-19) in Africa. Most people, especially in rural areas, depend on it for everything, including the crucial handwashing and cleaning required.

So, with climate change, factors change… groundwater is one of the critical areas through which we can address water security, resilience, in addition to improved sanitation in Africa.

IWMI’s cooperation with AMCOW on their groundwater program has spurred more cooperation across regions in Africa on their groundwater resources, cross-fertilizing knowledge from SADC to other parts of Africa.

How did we do it?

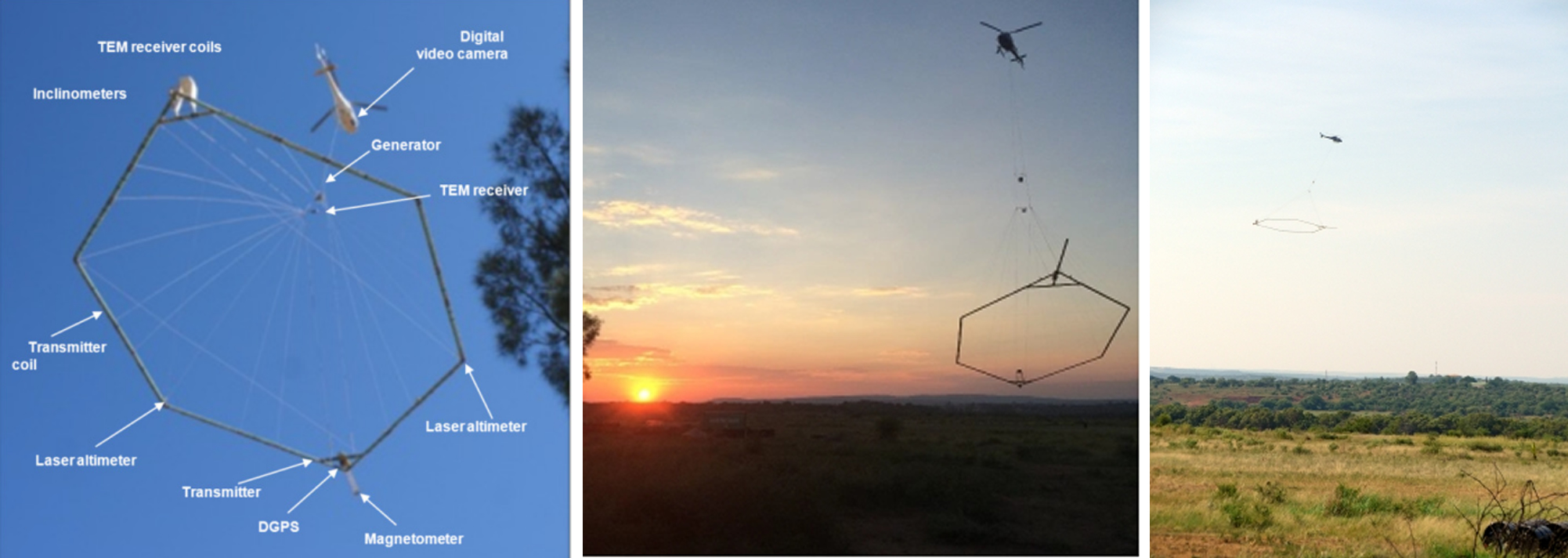

In 2016, the IWMI team created a three-dimensional conceptual model of the transboundary Ramotswa Aquifer, using an advanced non-intrusive technology.

Data were collected through a system called SkyTEM, transmitting an electromagnetic signal through the ground, from a device carried by a helicopter flying over the area.

Some crucial information was uncovered, such as the boundaries and layering of the aquifer and potential locations for drilling wells, e.g. dikes.

[twenty20 img1=”42387″ img2=”42388″ width=”100%” offset=”0.5″ before=”Map view” after=”3D Model” hover=”true”]

This slider depicts a satellite image of the Limpopo region (taken from Google Earth). Move the slider to see what is going on below ground level.

The 3D model was designed by IWMI researchers to study the aquifer.

Taking to the skies to understand water underground

Hanging below a helicopter is a giant hexagon. The helicopter and its cargo putter through the clear blue skies above Botswana and South Africa, following the underground transboundary aquifer.

The lozenge below the helicopter records electromagnetic readings from below in order to clearly map the 3-dimensional configuration and outline of the aquifer.

The helicopter flew for 12 days in a detailed checker-board fashion, before enough information was collected.

Watch the video

An integrated hydrological computer model was then created, in order to understand the underground processes of water flow in the Ramotswa area. This also helped the researchers understand the interactions between the aquifer and the river running along the border between Botswana and South Africa, as well as the predominant groundwater flow direction between the two countries.

The model, as part of a larger transboundary diagnostic, allowed the team to develop potential scenarios for groundwater management, e.g. how to augment the replenishment of groundwater through managed aquifer recharge – meaning how to put more water underground for future storage and use, e.g. from flood waters. The assessments led to a joint strategic action plan. This supported local and national policy-makers in identifying priority investments for the area.

The joint strategic action plan, developed as a cooperative process between the countries, identified priority actions, each belonging to one of the following categories:

- Managing water for sustainable use, availability and access

- Enhancing institutions and capacity

- Expanding research and knowledge

The joint strategic action plan emphasized the need for cooperation around effective data management and sharing between the countries. This meant developing a joint data management system, the Ramotswa Information Management System (RIMS), containing data collected with support from national governments and universities. It aligns data collection and management systems, ensuring data compatibility, and implementing data sharing procedures between the different transboundary actors. The purpose of the database is to help improve decision making on how best to manage the aquifer.

This is the worst time for us. Our rivers and boreholes are dry, and we are struggling to get water to drink. It is so painful. We used to get water from the local boreholes but now they have also gone dry

Themba Mabunda

The joint strategic action plan also highlighted a need for strengthening existing transboundary institutions – principally LIMCOM – to incorporate, for the first time, the management of transboundary aquifers into their portfolio.

To formalize this significant step, LIMCOM established an international committee between the four countries for the management of groundwater resources in 2019, the LIMCOM Groundwater Committee. This committee focuses on establishing best practices for transboundary aquifer governance in the basin and more broadly in the region. Out of 12 international river basin organizations in the SADC region, LIMCOM is the second to establish a dedicated institutional mechanism to oversee shared aquifer management.

IWMI’s work has closed a significant gap in understanding the dynamics in transboundary aquifers in the region and in the Limpopo Basin in particular. The studies undertaken in the Ramotswa and Tuli Karoo Aquifers shared by South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe assisted the Member States to understand the system behavior. IWMI has supported setting up institutional mechanisms and a critical platform for knowledge sharing and priority setting around these resources. The deepening of these processes is critical for enhancing the joint management going forward.

Sérgio Bento Sitoe, Executive Secretary, LIMCOM

The next step of the project was to support agricultural water management. The researchers adapted a set of tools, which local farmers could use to optimize their groundwater use for irrigation. Through simple soil moisture probes and nutrient measurements, farmers learned how they could save up to 40% of water, 30% of energy (for pumping groundwater) and 80% of fertilizers on their crops and even enhancing their crop production. This creates great savings and additional incomes for the farmers.

50

the annual number of days in the very short rainy season

Finally, in 2020, IWMI piloted a transboundary groundwater monitoring system in the Tuli Karoo Aquifer area to gauge groundwater levels.

The aquifer underlies an arid triangle of land in the upper Limpopo Basin, shared between Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Irrigation from both ground and surface water is key to the production of cereals, legumes, and vegetables as well as high-value crops and livestock.

Yet, in most years, water shortage results in farmers not fully cultivating all irrigable land in their schemes. Four existing wells in strategic locations were equipped with automatic data loggers and connected to a telemetry system and a visualization platform to monitor and transmit data on water levels, temperatures and electrical conductivity in real time.

This allowed farmers to gauge their water consumption and their prospects for short and long-term irrigation. The pilot is under expansion to cover 58 strategic locations in total.

Ramotswa Town is a growing peri-urban town of about 40,000 people in southern Botswana in the outskirts of Gaborone, located on top of the Ramotswa Aquifer. The persistent drought in 2013-2016 made flush toilets unusable in the Ramotswa area. Instead, the local population used old pit latrines. This led to substantial increases in the volume of human waste leaking into groundwater supplies. This increased the risk of nitrate contamination of drinking water from the nearby wellfield, Nitrate contamination can have serious impacts on human health, including cancer and blue baby syndrome.

IWMI research into how Ramotswa could move past its groundwater contamination problem emphasized a holistic approach. It recommended the rehabilitation of the sanitation system, by lining of new pit latrines, improving the system for emptying full latrines, and enhancing recycling. The final step consisted of assisting the aquifer with its own restoration processes, a technique known as in-situ bioremediation. Research indicated that most of the groundwater in Ramotswa had little organic carbon, an essential ingredient for nitrate removal. By introducing a non-hazardous source of organic carbon to the aquifer, simple techniques could increase its natural capacity for nitrate removal and thus decontaminate Ramotswa’s drinking supply. In-situ bioremediation was found to be less costly and more energy-efficient than pumping water to the surface in order to remove nitrate.

After years of work, our project has made a big difference:

-

- A project is deemed a success by the sheer number of people it helps, the valuable relationships it builds, and the essential data and information it generates. The transboundary RAMOTSWA project achieved all three, and more.

-

- Farmers significantly improve their livelihoods by applying simple water and nutrient management tools. Farmers saved on average 40% on water for irrigation, which translated into 30% savings on electricity cost, while increasing crop yields by 35% and decreasing nutrient losses by 80%. These tools reduce their use of groundwater, electricity for pumping, and fertilizers. Through extension services and word of mouth, other farmers are now taking up the technologies.

-

- Cooperation between countries in the Limpopo Rivers Basin and in the SADC region around shared aquifers has greatly advanced. A first-ever LIMCOM Groundwater Committee to serve this purpose has been set up in the Limpopo River Basin.

-

- More Member States in SADC are taking up the challenge to identify, map, assess and cooperate around their shared aquifers, partly supported by the SADC Groundwater Management Institute (SADC-GMI).

-

- Other initiatives in the region are benefitting from the RAMOTSWA project, e.g. by investigating and applying the wealth of information embedded in the RIMS to improve integrated water resources management in the area. They are also extrapolating methodologies and learnings to other areas in the region.

-

- Decision making on groundwater development and use is based on improved knowledge. For example, Botswana is now piloting Managed Aquifer Discharge (MAR) projects to support water security in Gaborone and its surrounding communities.

-

- Botswana and South Africa are exploring opportunities to counter their nitrate pollution issues through nature-based solutions.