Making wise use of the world's wetlands

For centuries, communities have benefited from the ecosystem services that wetlands provide, including those that support fishing, crop cultivation, and livestock farming. Wetlands are particularly important in places where water availability imposes constraints on agricultural production. For this reason, a balance is needed between using wetlands and conserving them.

Today, the world’s wetlands – which provide a safe haven for biodiversity and support environmentally sustainable livelihoods – are under threat. Instilling a sense of the ‘wise use of wetlands’ is something the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) has keenly invested in over the course of several decades. ‘Wise use’ entails using good judgement and the best empirical evidence to develop a broad, context-specific understanding of which practices deliver results.

This is vital when it comes to balancing the protection of vulnerable ecosystems and the needs of people who use wetland resources. We draw upon our years of experience to carefully consider the trade-offs for people and the environment in relation to different wetland management options, which could entail helping integrate sustainable agriculture practices within the wetlands themselves, for example, or encouraging gender parity when it comes to wetland stewardship.

IWMI has implemented successful research for development projects related to wetlands throughout Africa and Asia, including locations such as Ethiopia, Sri Lanka, southern India, and Myanmar. To reduce poverty and strengthen resilience, these projects have shared the broad aims of striking a balance between protecting vital ecosystem services and allowing for human use of these wetlands. IWMI promotes the notion of the ‘wise use of wetlands’ – a way of protecting wetlands that supports local communities while keeping aquatic systems healthy and aligning with the Ramsar Convention’s concept of ‘wise use.’

How the Ramsar Convention defines a wetland

Named after the city of Ramsar in Iran, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat is an international treaty ensuring the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands. It was signed in 1971 by seven states; today, it includes 171 nations that meet every three years. Article 1 of the Ramsar Convention states that “wetlands are areas of marsh, fen, peatland, or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six meters.”

Global inland and coastal wetlands cover 12.1 million km2

IWMI’s work has directly shaped the content of several Resolutions adopted by the Ramsar Convention, including those relating to:

- Wetlands and human health and well-being

- Wetlands and poverty reduction

- Wetlands and water resource management

- Wetlands and agriculture

- Wetlands and climate change

- Enhancing biodiversity in rice paddies

Why are wetlands important?

Regardless of whether wetlands are situated in urban or rural areas, IWMI focuses a significant amount of attention on these ecosystems because wetlands are vital for a wide range of reasons.

- Wetlands provide tangible and intangible services to people, helping support our need for food, water, fuel, medicine, recreation, and livelihoods.

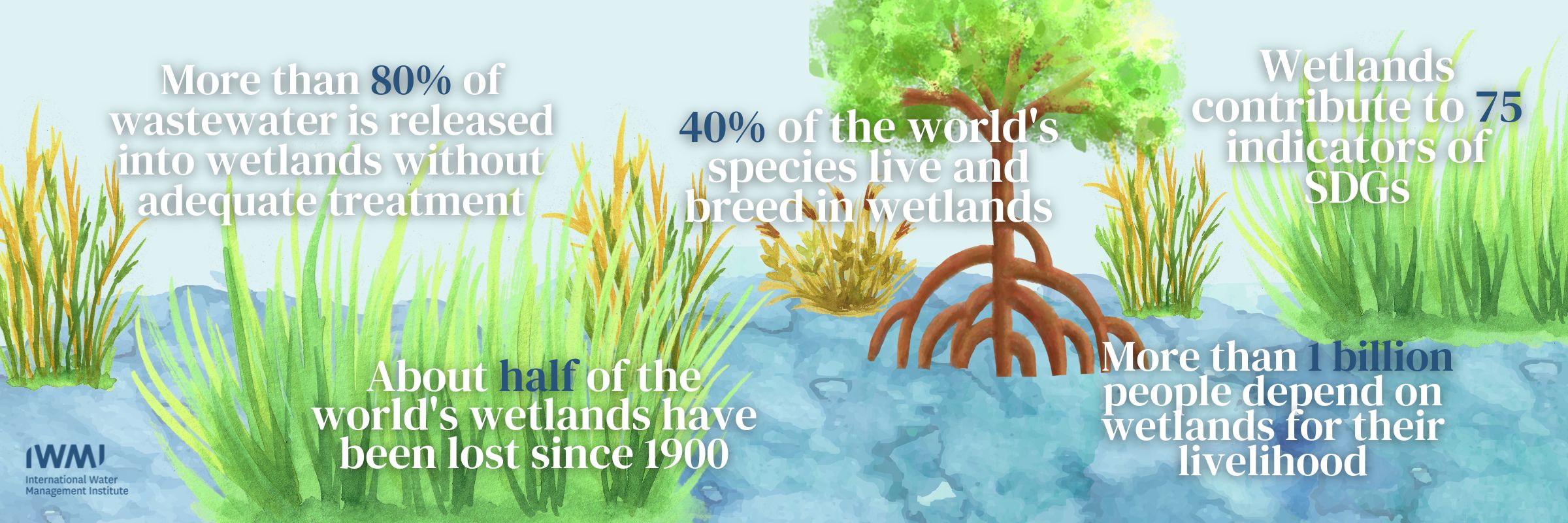

- From peat bogs to estuaries to floodplains, wetlands are where land meets water, providing a habitat for an estimated 40% of the world’s plant and animal species.

- Wetlands are highly productive ecosystems: Shallow water, high levels of nutrients, and the proximity of plants to water mean that wetland waters are often deeply nourishing, and support critical cycles such as fish migration and breeding.

- Wetlands are often inextricably linked to food production systems, and support food security and livelihoods of millions of people worldwide.

- Some wetlands protect us from flooding and drought. In certain circumstances, for example, coastal wetlands such as mangroves may protect the built environment from storm surges, absorbing energy before water impacts coastal communities.

- While just as important as other endangered ecosystems, such as rainforests or coral reefs, wetlands tend to get less attention – despite the fact that we are losing wetlands three times more quickly than forests.

- Wetlands cover just 6% of the Earth’s surface, but sequester and store significant amounts of carbon, thereby helping to mitigate climate change.

Where IWMI’s work on wetlands has taken us so far

Over the past twenty years, IWMI and our partners have achieved significant successes when it comes to preserving wetlands for future generations. Here are some examples.

Signing up to the Ramsar Convention

IWMI was confirmed as the fifth International Organization Partner (IOP) of the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands during the 9th Conference of Parties in Kampala, Uganda, in November 2005. Today, IWMI stands alongside the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, World Wildlife Fund, BirdLife International, Wetlands International, and Wildfowl and Wetland Trust as a Ramsar IOP.

[Being a partner of the Ramsar Convention] is a powerful link to have, as many global level discussions and decisions take place and we have access to the current thinking and latest information. Focused on aquatic ecosystems as we are, we have perspectives that we can place before the global gatherings. We function as observers and support the activities (such as specific resolutions, declarations, and policy briefs) of the Ramsar Convention which are related to wetlands, their ecosystem services, and wise use. Compared to other IOPs, IWMI’s focus is primarily on the role of wetlands in supporting livelihoods – with a special focus on the critical role of water and the wise use of wetlands for agriculture.

Dr. Priyanie Amarasinghe, Emeritus Scientist at IWMI

The Ramsar Convention promotes the wise use of all wetlands and works to ensure the protection of these vital ecosystems. Today, there are over 2,500 Ramsar sites across the world, covering more than 2.5 million square kilometers. Ramsar sites are identified as wetlands of particular importance, in terms of either the level of biodiversity they contain or the cultural heritage they protect. Ramsar sites all meet the strict ecological, socio-economic, cultural, and strategic criteria which make them wetlands of international importance. And yet, designation is by no means a protection against any risks, including ecological damage caused by technological developments, pollution, and other human activities. Designation is rather an incentive for country governments to take added measures to use these wetlands sustainably.

IWMI’s contributions to Ramsar over the years have been significant, moving beyond advocacy of wetland conservation and protection to also encompass (and emphasize the importance of) sustainable development, integrated wetland management, and citizen participation.

Wise use of wetlands

The Ramsar Convention defines ‘wise use of wetlands’ as “the maintenance of their ecological character, achieved through the implementation of ecosystem approaches, within the context of sustainable development.” However, a challenge persists in interpreting exactly what ‘wise use’ means.

Outright protection of wetlands is incompatible with agriculture and, in places, undermines livelihoods and efforts to reduce poverty. We have frequently seen these approaches fail in the past. But there are landscape approaches and agricultural practices that can support and sustain healthy wetlands, and vice versa. Working with local communities helps us find the best solutions.

Matthew McCartney, Research Group Leader - Sustainable Water Infrastructure & Ecosystems

Working to preserve an urban treasure: Colombo’s endangered wetlands

Due to rapid urbanization, the last 30 years saw a 40% decline in the area of Colombo’s wetlands. This is significant because Colombo has particularly extensive wetlands compared to other similarly sized cities around the world. Between 1980 and 2021, the city’s population rocketed from just 500,000 to more than 750,000, placing considerable pressure on its wetlands in the process.

However, after recognizing the importance of the wetlands for flood control and a range of other ecosystem services, including urban agriculture, the Government of Sri Lanka developed a wetland management strategy in 2016. In 2018, as a result of the efforts of the Government of Sri Lanka in collaboration with IWMI and other partners, Colombo became one of 18 sites around the world to be awarded Wetland City Accreditation by the Ramsar Convention. The scheme aims to increase awareness and promote the sustainable and ‘wise use of wetlands’ for economic and social benefits. These benefits include better flood control, strengthened food security, and increased biodiversity conservation, and today, the Wetland City Accreditation has potentially opened a new chapter for preserving Colombo’s endangered wetlands.

Emeritus Scientist Dr. Priyanie Amarasinghe explains how IWMI was instrumental in bringing stakeholders together. “We weren’t the first organization to start work on Colombo’s urban wetlands, but we felt like the organizations working on it were each working on their own thing,” she says. “Each institution had their own role to play, but they were working in isolation. IWMI played a role as facilitator, playing an important part in bringing the different partners together.”

[Colombo urban wetlands] is probably one of the most impactful things we have done when it comes to wetlands,” says Matthew McCartney. “We played a role with national government agencies, the World Bank, and others. The success came because of the effective collaboration.

Dr. Priyanie Amarasinghe, Emeritus Scientist at IWMI

“We are happy to see this important effort come to fruition,” adds Amerasinghe, speaking of Colombo gaining Wetland City Accreditation in October 2018. “Ramsar accreditation of the Colombo wetlands reaffirms our message about the wetlands being of vital importance, and it lends urgency to efforts aimed at halting their continued loss and degradation.”

Exploring the gender dynamics of wetland management in Myanmar

Central to the ‘wise use of wetlands’ is working with different groups within communities living in wetlands to ensure that management decisions do not adversely impact specific stakeholders. A key challenge are the differences in the capacities and influence between these groups, which creates the risk that some groups’ views and interests will dominate over others.

An important aspect of this complex challenge is the influence of class, ethnicity, religion, gender, and other social identities and norms in providing more influence for some while marginalizing others. These social dynamics need to be understood when working with the full range of stakeholders in a community to reach balanced management decisions. In Myanmar, IWMI, WorldFish, and local partner Point B Design + Training are supporting the Gulf of Mottama Project (GoMP) to better understand and address these complex social relations when implementing ‘wise use of wetlands’ in the Gulf of Mottama, a recently designated Ramsar site.

IWMI and its partners worked with the GoMP to identify which groups of women and men are less able to influence wetland management decisions, and why this is the case. The research explored how these disparities determine who is at the table and whose voices count as it relates to making management decisions concerning wetlands. We highlighted how gender, class, and other social identities intersected and combined to shape the power that different women, men, and groups of resource users have wielded to influence decisions.

Central to this analysis of power was the ranking of different types of knowledge by communities, in terms of their perceived relevance to decisions over wetland management, where knowledge borne out of experience in interacting with the wetland was prioritized over other forms such as knowledge acquired through training. Given the highly gendered roles of women and men, it was the men who generally acquired experiential knowledge and hence enjoyed leadership and decision-making positions.

The following comment by one male typifies this gendering of knowledge, as well as broader endemic gender hierarchy at play: “We think women don’t have knowledge about the wetland and they tend to focus on personal feelings,” he said. “Women are less experienced and need training in the future to develop knowledge. According to our culture, women tend to follow what is said.” This analysis also brought out the role of class, as even amongst men, those from lower-income families had less power, given their reputation within the community as being less literate and able to articulate themselves.

These insights helped sharpen GoMP’s understanding of social disparities that occur at different scales – including within households and communities, between communities, and also between sectors – and now informs the GoMP’s strategies for establishing more socially inclusive wetland management.

A key lesson IWMI has learned from our work in the Gulf of Mottama is that there is no simple, quick-fix solution to ensure the ‘wise use of wetlands.’ Women should be included in wetland management decision-making right from the outset, which will give a nuanced approach to social exclusivity.

Responses to gender and other social challenges must also be able to transform social relations, and this requires time, specialized skills, and funding. In addition to using these insights to strengthen the GoMP’s social engagement strategies, IWMI has communicated these findings and messages to practitioners through several webinar presentations and an open-access journal article.

How wetlands can dampen the impact of extreme weather events and provide benefits for local residents

Wetlands are also a focal point of IWMI research because they play a critical role in the realm of climate change mitigation.

In Zambia, the Barotse wetlands are located on the upper reaches of the Zambezi River basin. Thanks to the seasonal rainfall, these wetlands experience regular flooding. However, extreme weather events in this region have led to an increase in rainfall, which has fueled more flooding than normal.

At the same time, the Barotse wetlands are a valuable resource.The wetlands are fertile and allow for the cultivation of maize, rice, sweet potato, sugarcane, fruit, and vegetables – supporting around 27,50 households – and it is estimated that reeds and papyrus collected from the Barotse floodplain wetland in Zambia are worth more than USD$373,000 to local communities. The wetlands have spiritual and cultural significance, too: each year when the floods come, the Lozi people of the Barotse floodplain celebrate the flooding of the Zambezi with a Kuomboka ceremony.

To encourage sustainable wetland management in the Barotse wetlands, IWMI researchers have advised on how best to implement improved land-use planning in the area, especially given the increasing frequency of extreme weather events. One of the more successful IWMI-backed activities has involved the introduction of participatory GIS maps that allow users to not only better understand flooding and weather patterns, but also pursue more sustainable land-use practices to avoid livelihood losses related to flooding.

What next for IWMI’s involvement with wetlands?

From Zambia to Myanmar to Sri Lanka and beyond, IWMI is committed to supporting the ‘wise use of wetlands’ across the globe, and IWMI’s work on wetland issues in southern Africa, South Asia, and East Asia continues to influence organizations and shape policy. While the Resolutions related to the Ramsar Convention are not legally binding, governments who have signed the agreement are encouraged to implement them. The Resolutions continue to contribute to bring greater attention to the role of wetlands in poverty reduction among Ramsar parties, thereby promoting a better balance between conservation and development in the way wetlands are managed. We have made – and will continue to make – a concrete contribution in this regard.

Going forward, IWMI intends to use its considerable platform to continue ensuring that research and knowledge relating to wetlands’ productive and sustainable use are widely disseminated, for the benefit of current and future generations.

“This is IWMI’s niche,” explains Matthew McCartney. “In some regions, where rainfall is seasonal and there is no irrigation, communities must use wetlands to grow food and sustain themselves. The problem comes when population pressure and/or big businesses or governments start draining or building on them. This alters the hydrology and the natural functions that sustain the wetlands and the biodiversity they support. We need to work with local populations, empowering them to sustainably manage the wetlands in their own landscapes. People need to be central to our thinking about wetlands.”