How a simple tool is reducing conflict and preserving water in Uzbekistan

Smartsticks help farmers get a fair allocation of water while protecting land from aridity and strengthening farmers’ resilience in the face of climate change.

To be a successful farmer, you must have four key things: A crop, land, willing hands, and a reliable supply of water. Without water, land will lose its richness, crops won’t grow, and willing hands will leave. Water is vital.

Nowhere is water more precious than in an arid country such as Uzbekistan, where agriculture consumes some 90% of the water supply. But while scarce water resources must be distributed fairly, allocating water among individual farmers, agricultural regions, and households can prove to be a complicated undertaking.

One way of attempting to ensure fair distribution of water is through Water Consumer Associations (WCAs), which also operate and maintain on-farm irrigation networks. However, what happens if the allocation of scarce water resources is disputed, and farmers argue that they are being overcharged and underserved?

That’s where IWMI scientists, working together with the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, may have hit upon a solution. Thanks to work conducted under both the EU programme “Sustainable management of water resources in rural areas in Uzbekistan” and the BMZ-funded project “Sustainability and value added in the cotton economy in Uzbekistan,” IWMI and GIZ believe a tool known as a smartstick could be utilized to address water scarcity challenges and help resolve disputes concerning water access.

Smartsticks monitor exactly how much water is discharged to farmers. As a result, significant improvements in water accounting have been made in Uzbekistan, while conflicts between WCAs have decreased and food production has increased.

The smartstick is the creation of Dr. Patrice Muller from the Swiss University of HE-Arc, and IWMI subsequently adapted his tool to suit local conditions. IWMI researchers understood the tremendous potential of the smartstick, given the tool’s ability to allow farmers to observe the precise amount of water flowing onto their land, since the device is used in tandem with mini-gauging stations that sit on the boundaries of farmers’ fields.

As farmers, currently we oversee the process of water delivery turn by turn: Every evening two people from each WCA brigade control the water flow irrigating our fields. The amount of water that is being supplied presents another issue….as the WCA does not measure the exact amount of water they deliver to each field. For example, we need 50 liters of water and the neighboring field needs the same amount. However, if they receive 100 liters, we will not get the needed 50 liters, because the water supplier did not measure the amount of water that is being supplied to the single farm. It is difficult to meter the water, as there are no proper water measurement devices or equipment for that.

Mr. Yangiev, farmer

An arid country on the frontlines of climate change

Located in Central Asia, Uzbekistan is an arid country that is highly vulnerable to climate change impacts, including decreased rainfall, desertification, drought, and rising temperatures. With the flow of water in its two main rivers—the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya—projected to decrease by 15 percent by mid-century, it is clear that the country will have to maximize its water-use efficiency in order to ensure the vitality of its agriculture sector and remain water-secure well into the future.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, farmland in Uzbekistan has changed hands, shifting from giant state-owned cooperatives which needed enormous volumes of water to be productive to smaller plots that Uzbek farmers can cultivate. These smaller plots tend to be around 35 to 40 hectares in size, and each plot requires its own source of irrigation. WCAs were established to meet the individualized needs of farmers, but the introduction of these associations has not entirely solved the problem they were designed to alleviate.

Understanding tensions between Uzbek farmers and local Water Consumer Associations

While WCAs were set up to help meet farmers’ needs, the associations have sometimes struggled to deliver sufficient water. In turn, farmers have sometimes refused to pay their irrigation service fees. This affects the quality of water delivery even further, and the problem persists.

One of the biggest challenges WCAs have faced is not knowing exactly how much water has been delivered to each farmer. This can result in conflicts between WCAs and farmers, as accusations of unfair charges are frequently levied at the associations, and farmers can come to resent paying their fees, which in turn further restricts their access to water.

To that end, a 2017 paper by IWMI researchers in Central Asia surmised that “greater trust and communication within the WCAs would make an important contribution to effective collective action and to the long-term sustainability of local associations.”

Is there a solution?

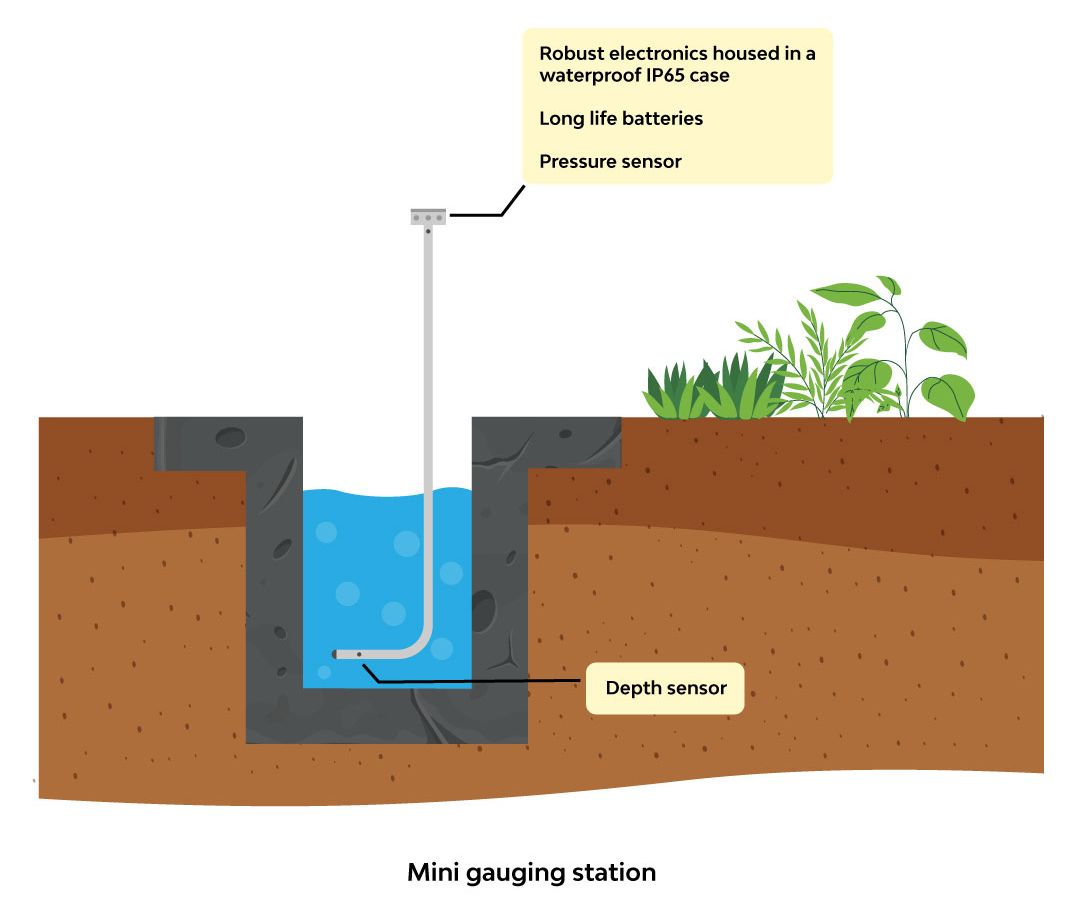

As part of the ‘National Policy Framework for Water Management,’ IWMI completed research trials which identified clear improvements for addressing over-use of water and reducing water waste. The introduction of smartsticks, placed in mini-water gauging stations, was one proposed solution, as gauging stations are where water data is collected to understand how much run-off or discharge is present.

Between 2017 and 2019, we worked with three Water Consumer Associations, serving about 500 farmers, and right now we are investigating how to replicate our approach in three additional provinces with selected agricultural cotton-textile clusters, so that we can test new electronic tools that enable them to automatically account for how much water has been delivered to which farmers. Central Asia is a dry and arid region, where accounting for each drop of water is vital. It’s especially important as climate conditions change and different sectors of the Uzbek economy increase their water demands. Water accounting is necessary not just to ensure irrigation fees are paid, but also to ensure farmers receive the right amount of water to irrigate their crops. Therefore, there is demand for low-cost technology at a local level.

Oyture Anarbekov, Researcher and Country Manager with IWMI’s Central Asia Office

Taking a closer look: What is a smartstick exactly?

A smartstick is an electronic handheld tool that is driven into the middle of a mini-gauging station, which is the concrete structure built on the narrow space at the boundary between a farmer’s plot and the canal through which the water comes to the field. Upon installation, the smartstick can accurately measure how much water has been delivered, and to whom. Once we know the water level in the mini-gauging station, we can quickly calculate the discharge flow in the channel.

The device works by taking a level measurement and comparing it to the discharge curve of the canal to determine how much water has been discharged. This is important because in order to accurately calculate water discharge flow in the channel, we need to know the profile of the gauging station as well as the water level depth. These two parameters provide exact water discharge flow, with the smartstick producing an electronic reading showing how much water the farmer has received. The tool also displays its depth in the ground in real-time.

Perhaps best of all? The smartstick has a long-life battery and is fully automatic, so the tool can also be used for monitoring water levels in small rivers, streams, and irrigation channels.

But what does the smartstick do in real terms?

The information the smartstick provides reassures the farmer that they are paying an accurate fee to their local WCA based on the amount of water received, since each farmer’s fee is based on the precise amount of water that is delivered. Furthermore, knowing exactly how much water is supplied to the farm means the farmer can more effectively adhere to crop water requirements.

Crucially, the smartstick ensures an accurate and transparent communication to the farmer, and consequently can help resolve and reduce conflicts related to water distribution. Since the tool allows farmers to see clearly how much water has been used, the smartsticks can also incentivize farmers to pay irrigation fees, which are vital for the long-term maintenance of channels and pumps.

Gauging the key successes of smartsticks in Uzbekistan

In addition to disputes over too little water, over-irrigation is also a contentious issue in Uzbekistan, making the regulation of water distribution all the more vital. IWMI’s pilot project reached 500 farmers in the country under the aforementioned EU programme, and yielded promising results: The introduction of smartsticks considerably reduced over-irrigation, encouraged farmers to pay their fees, and ensured more efficient distribution of water.

Before I used to measure water by eye and I didn’t know the exact amount of water that was being delivered. With the help of this new low-cost, technologically advanced portable device I am able to accurately and quickly determine the amount and level of the water that we supply to the farmlands. By applying this technology, we no longer have disputes with farmers over the water delivery process. The data that we get from smartsticks we send to the computer and regulate the amount of water each farmer receives for his land.

Akramjon WCA Kuva Urta Buz Anori

Before I used to measure water by eye and I didn’t know the exact amount of water that was being delivered.

Akramjon WCA Kuva Urta Buz Anori

In real terms, the utilization of smartsticks has resulted in more reliable and successful crop production, including cotton and wheat. Farmers have also confirmed an increase of yields due to on-time delivery of a reliable water supply.

Meanwhile, since 2019, scientists have met with Uzbek policymakers to report on outcomes of the trials. The results were so successful that the implementation of smartsticks and mini-gauging stations was made a priority in the country’s 2020-2030 National Agricultural Development Strategy and its corresponding roadmap.

What’s next for the smartstick rollout?

Moving forward, smartsticks and mini-gauging stations can be easily scaled up to support Uzbekistan’s farmers and agricultural clusters, such as cotton-textile clusters.

In 2020, for example, there were a total of 454 agricultural clusters across the country. An agricultural cluster is an advanced type of agricultural industrialization unit, usually operated and managed by a limited liability company. Uzbekistan’s agricultural cluster system was introduced within the last two years in order to increase the competitiveness of the country’s agricultural production in both regional and world markets, and to accelerate the adoption of modern innovative water-saving technologies such as drip irrigation, sprinklers, and smartsticks. Uzbekistan’s 454 clusters—which are comprised of 114 cotton-textile clusters, 157 wheat clusters, 146 horticulture clusters, 29 rice clusters, and eight clusters for medical plants—cover an irrigated area of 2.2 million hectares, accounting for 59 percent of the total cultivated area. Of this, 0.3 million hectares (14 percent) are directly farmed by the clusters, while the remaining 1.9 million hectares are cultivated through contract farming, engaging a total of 72,501 farmers.

Thanks to government backing, deploying smartsticks to support farmers and agricultural clusters will be made significantly easier in the years ahead. With policy support behind the rollout, smartsticks are now well-positioned to help Uzbekistan manage water scarcity nationwide, improve food production, combat drought, and more effectively weather the many other impacts of creeping climate change across the region.