Empowering rural women with multiple-use water services

Increasingly common around the world, multiple-use water services (MUS) place villagers in charge of the design and governance of their own water infrastructure, with local government bodies and non-profit organizations supporting these efforts by developing villagers’ water-management capacities, supplying materials, and monitoring implementation.

Given that water provides the foundation for all life, it naturally makes sense that water services be designed with this resource’s many uses in mind. The MUS approach addresses water access challenges by implementing community-led water system design and management practices that have been proven to save water, improve health and food security, alleviate labor, and empower girls and women in rural and peri-urban communities across the Global South.

Since its introduction in 2004, the MUS approach has seen success across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The International Water Management Institute (IWMI), for its part, has been working to expand MUS implementation since nearly the beginning.

IWMI is one of 19 core organization members of the MUS Group, which collects and shares data on over 200 MUS case studies from 30 countries, and IWMI also leads the MUS Theme on behalf of the Rural Water Supply Network (RWSN).

These consortia and networks build on past experiences to support current and future efforts to improve and scale-up MUS. By sharing lessons learned from previous MUS projects, IWMI researchers and MUS networks are able to expand MUS projects and scale benefits to more communities around the world. And with mounting competition for limited water resources, IWMI expands the focus on multi-use infrastructure development to ensure rights-based water resource allocation that prioritizes basic domestic and productive uses.

One country where MUS projects have found particularly fertile ground in recent years has been South Africa. In that country, following the end of the apartheid era, the new Bill of Rights included the right to sufficient water and food, prompting government action on providing first-time access to water infrastructure in many rural communities. However, such actions have slowed over time, and what steps were taken were often led by external entities, like government consultants. Many water systems designed and implemented during this time were planned to meet a specific need of a community, like irrigation for smallholder farmers. The problem with this approach, however, was that locals needed water for many purposes — a fact that should influence the type of water supply, the governance of how it can be used, and the location of access points. But without local input or leadership, many government-led water initiatives were either left incomplete or derailed by mismanagement.

Recently, based on the successes of MUS in six South African villages in the Limpopo Province, IWMI has released guidelines for community-led multiple-use water services for future MUS implementation. In these villages, externally designed and managed water systems had either fallen into disrepair or had failed to be constructed as promised. But the MUS framework helped guide these communities as they began to reimagine their water systems.

IWMI’s researchers tracked the process, successes, and challenges of MUS development and published a detailed Working Paper in 2020, focusing on the first two villages to have MUS fully implemented: Ga Mokgotho and Ga Moela. The data collected on the remaining four villages was published in 2021 in a report for the South African Water Research Commission.

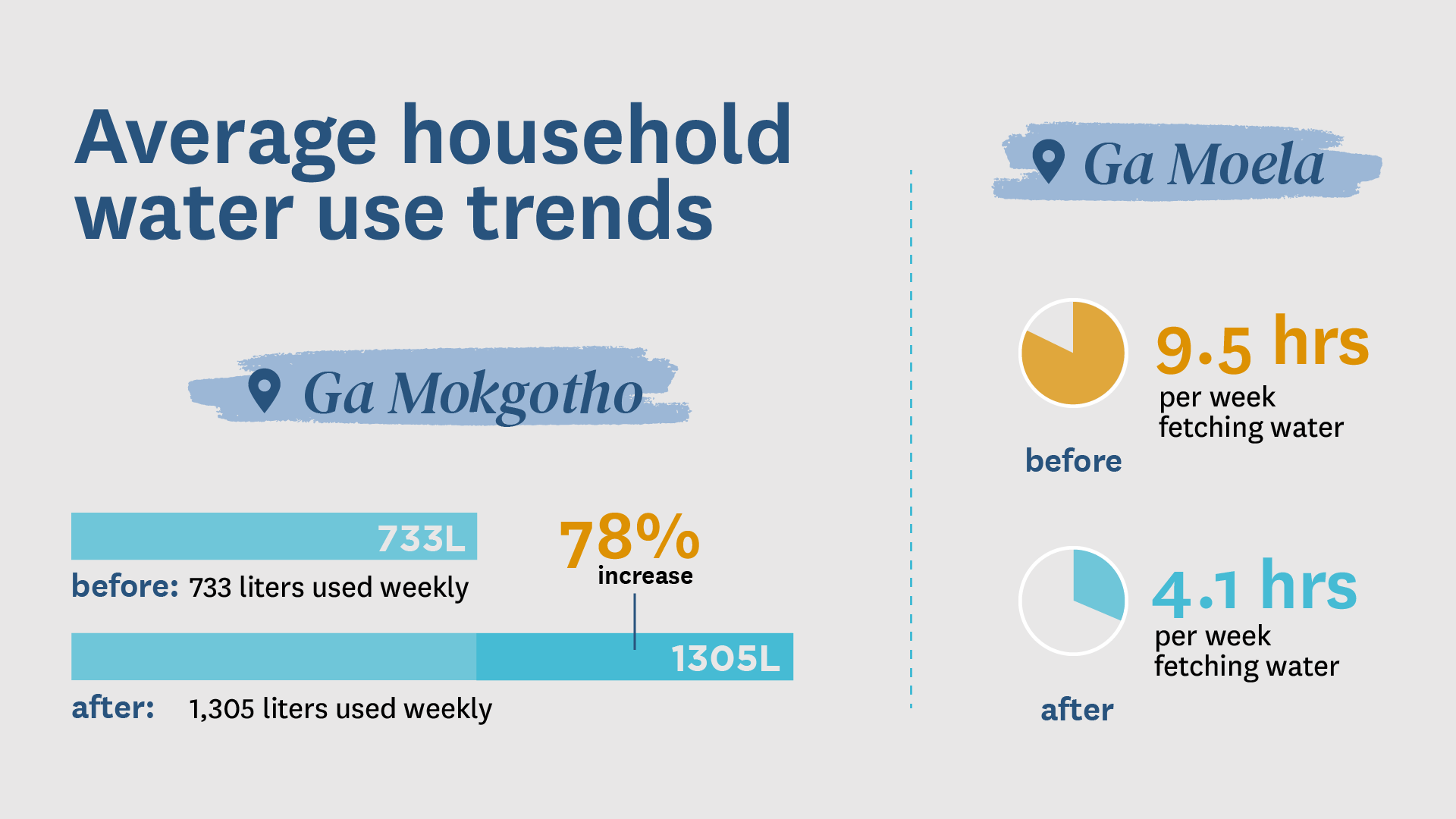

In Ga Mokgotho and Ga Moela, new water services were designed with the multiple water needs and priorities of community households in mind, and benefits were seen across these many uses. In Ga Moela, having access to water closer to houses more than halved the time residents had previously needed to fetch water. And in both villages, the value of irrigated fruit trees increased by at least 60 percent.

While the project was implemented by IWMI, Tsogang Water and Sanitation, and the Water Research Commission of South Africa, and supported by the African Water Facility of the African Development Bank, the initiative was led by local community members, who assessed the current water supply infrastructure, figured out ways to repair it, and installed new pipes, taps, and troughs where needed.

In Ga Mokgotho, local leaders and technicians improved governance, boosted water intake from streams, and enabled infrastructure repairs of a dilapidated, decade-old, NGO-constructed gravity system. Meanwhile, in Ga Moela, where locals primarily used shallow dug wells to access water for household and livestock purposes, the MUS project upgraded existing municipal boreholes to provide first-time access to four neighborhoods.

With MUS, the entire community stands to benefit. Women and girls who spent hours every week fetching water for drinking, cleaning, and cooking are left with more time to explore other pursuits, including caring for homestead gardens and selling the produce they grow. Female and male smallholder farmers can depend upon a more consistent water supply for livestock and irrigation. And all households benefit from greater water security and the public health improvements that entails.

What multiple uses?

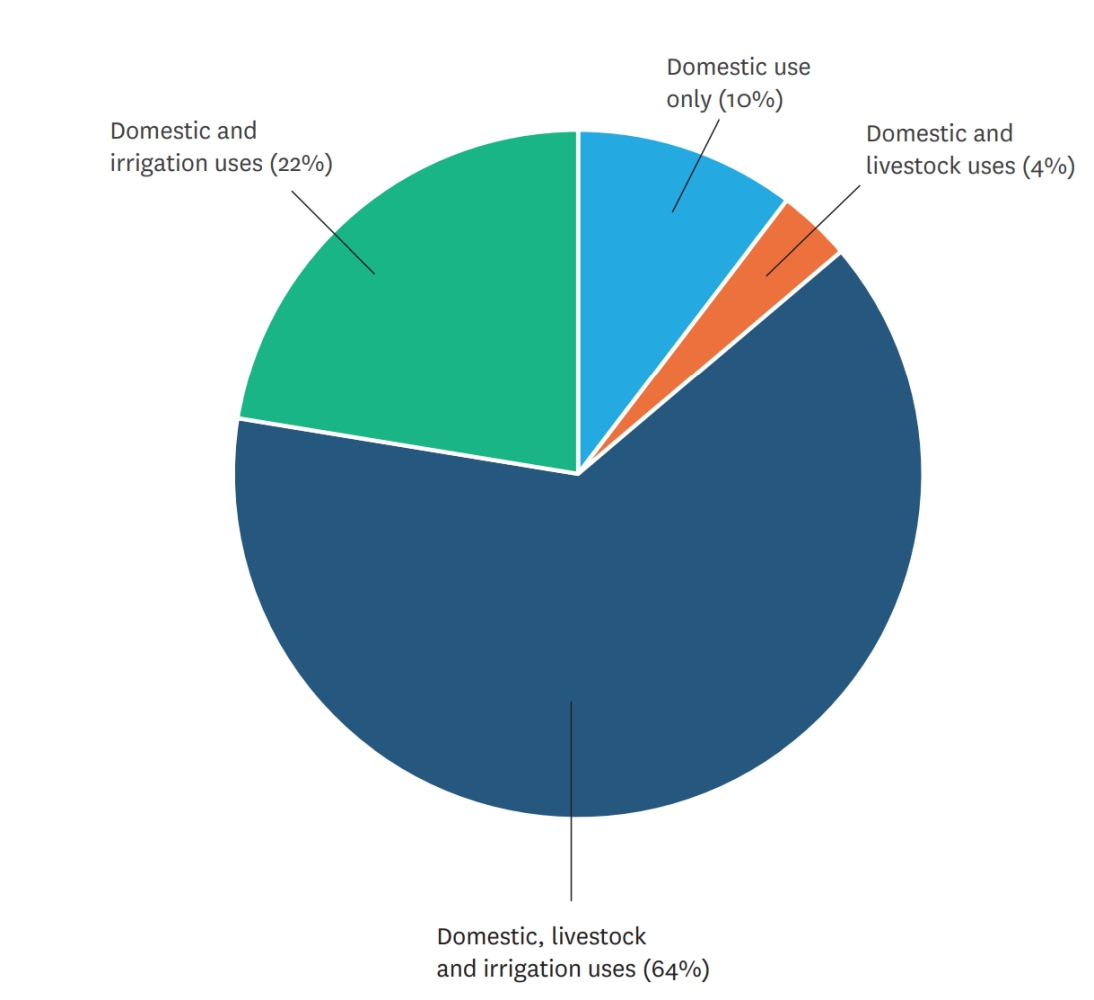

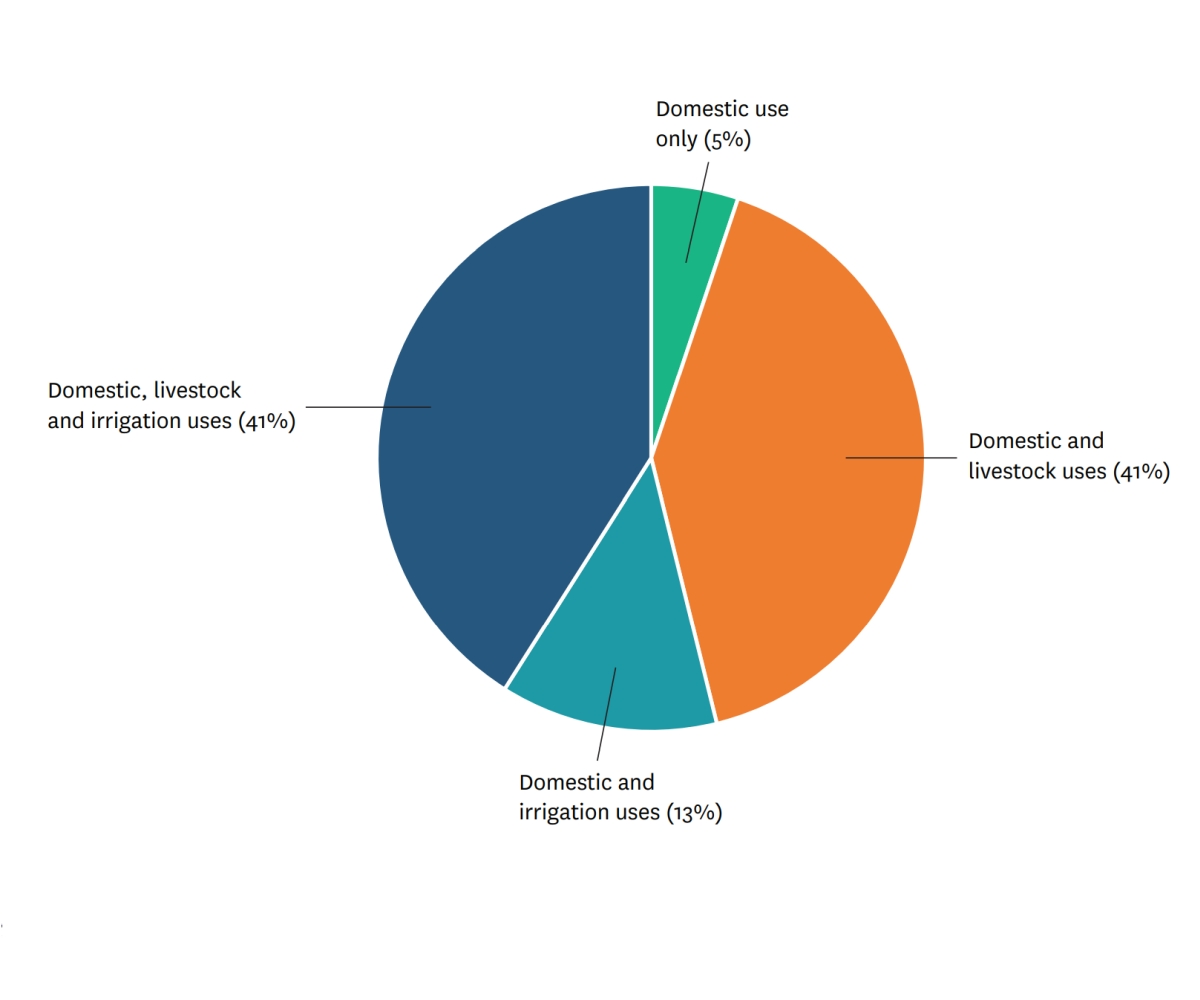

Across Ga Moela and Ga Mokgotho, 64 percent of households use water for three purposes. Click on the question marks to learn about how community members used the water from their MUS.

Meet the villages

Ga Mokgotho and Ga Moela are located in the Sekhukhune district of South Africa. Though they are relatively close in location, differing geography and local circumstances present unique challenges to villagers sourcing water.

Ga Mokgotho is a rapidly growing village of around 800 households in a mountainous area that receives an average rainfall of about 800mm each year. In 2007, an NGO began construction on a piped gravity system bringing water from mountain streams down to a large brick reservoir that initially supplied 94 taps throughout the village.

However, with weak communal management that did not represent the needs of the village, service became unreliable. Villagers reported that the reservoir was not cleaned; pipes leaked; water pressure was low; taps were broken, stolen, or at distant locations; and there was not enough water to meet all household needs. Above all, they reported periods of three days, two weeks, or even months without water.

To the south in the Leolo mountains, Ga Moela is comprised of around 118 scattered households. The annual rainfall is between 500-750mm, and its fertile soil supports rainfed agriculture (mainly maize) and livestock keeping. However, poverty has led to out-migration in the village, mainly by young men.

As a result, 60 percent of the adult family members in the households sampled by IWMI researchers were women, and half of the households were female-headed. The main water sources were previously 20 shallow hand-dug wells only 0.5-1 m deep.

These waters were dirty and shared with animals, and the dispersed nature of the households meant that almost all homes relied on water that was carried from sources in buckets or wheelbarrows.

Ga Mokgotho and Ga Moela are located in Limpopo province, in northeast South Africa

Household water-use patterns prior to MUS implementation in Ga Mokgotho (left) and Ga Moela (right).

By implementing multiple-use water services in these communities, villagers were able to help design water systems that worked for their needs, climate, and geography. They used local water wisdom as a starting point for planning, design, and management, and were subsequently able to enhance the water provisions that were already present in the village.

What are community-led multiple-use water services?

A holistic, participatory approach to planning and providing water services that supports people’s self-supply and their multiple water needs — as identified by the community — and coordinates across government departments as needed.

Under the guidance of an NGO, Tsogang Water and Sanitation, community members contributed to every step of the design and governance process, starting with the establishment of water committees to oversee the process and eventually achieving a level of water service that met the many water needs of the rural communities.

In order to implement the MUS in a way that maximized benefits for villagers, they collaborated on every step of the process. Though the process is visualized as a six-step progression, the steps are not rigid. Rather, in the cases of Ga Mokgotho and Ga Moela, the villages and the guiding NGO were constantly assessing the process and were encouraged to return to previous steps as needed to design the most appropriate and successful MUS for the villages.

At the start of the process, Tsogang organized mass meetings in both villages, where all community members were invited to meet the project team, the participatory approach of MUS was introduced, and local water committees were established to oversee the project, creating a link between the community and Tsogang that allowed for transparent reporting on the project’s progress.

Communities appointed committee members among themselves with the aim of reflecting the diversity of the communities they represented, rather than only considering prior experience in such roles. Even so, in Ga Moela — where none of the members had any previous committee experience — villagers said that “without them, water would not be available.”

Committee members, as well as villagers outside of the water committee, worked with Tsogang to assess the pre-project water situation. Participants mapped resources out on the ground, held focus group discussions and additional mass meetings, and measured the flows and geographic makeup of the area.

In both villages, the Tsogang facilitator noted how the men enthusiastically started the mapping, and how the women gently corrected them.

IWMI Working Paper 193

Participatory resource mapping in Ga Mokgotho helped villagers learn about each household in the village, water flowing in supply lines, buried pipes, and reservoirs in the village.

Photo: Barbara van Koppen / IWMI

The maps drawn by villagers were key in envisioning solutions for water challenges. Villagers were encouraged to provide their ideas for water solutions to committees, who in turn considered ideas that included building dams, constructing new pipes, installing cattle troughs, replacing valves, improving borehole taps, and identifying new locations for water storage sites and street taps.

The viable proposals submitted by the villagers underwent financial review as construction, labor, and maintenance costs were assessed and budgeted for; and in both villages, locals were determined to be the ones to execute the selected projects. Committee members decided upon pay rates and work schedules for the local workers before moving forward with implementing the new design for the MUS.

Teams procured materials, recruited workers through a random selection process, trained the new workers, coordinated volunteers, and swiftly constructed the new services in both villages. After initial tests revealed challenges facing the new systems, committee and community members continued to work to address and mitigate them.

Payment and continued engagement: Challenges in establishing MUS

Both villages insisted on employing locals in the installment process, and before recruitment began all parties agreed on a stipend similar to those offered by South African employment-generation programs. A few workers surveyed in both villages did highlight low pay as a disadvantage. In Ga Mokgotho, for instance, workers noted that because pay was in the form of a stipend, they made less than national minimum wage. Workers also voiced concerns that they were not given sufficient personal protective equipment and that in some cases, machinery would have been more efficient than manual labor. However, Working Paper 193 emphasized that overall, workers were pleased with their pay.

After the initial building was completed, testing and operations began at both sites. While some initial issues arose and were addressed — Tsogang repaired a crack in the Ga Mokgotho reservoir that had developed due to the increase in water inflows, for example — lasting engagement waned. Ga Mokgotho had also planned to install yard connections rather than street taps, but there were no volunteers to initiate and organize the process.

Ga Moela also encountered technical challenges during the early testing period, but locals and Tsogang were mostly able to address these obstacles. For example, when a diesel pump broke, users collected money from households to fund the repairs, rather than waiting for the municipality to fix it. And when steel supports bowed under the weight of filled water tanks, Tsogang reinforced them by welding on additional bars.

Laying the foundation for a more water-secure future in South Africa and beyond

Despite challenges like these, multiple-use water services had an overwhelmingly positive impact on their communities. In both villages, nearly all survey respondents agreed that there were very few, if any, disadvantages to the new systems.

With water access more plentiful and accessible, WASH practices subsequently improved in both villages. Washing bedding at home became a monthly task, and users were able to bathe, wash clothes, and clean floors and windows more frequently.

Beyond domestic uses, water availability also increased for livestock and irrigation, which was essential as livestock received water at 68 percent of households.

Not only did the two villages receive a more reliable water supply, the MUS implementation process also provided training in semi-skilled jobs for locals. Between Ga Mokgotho and Ga Moela, for example, 96 villagers — both male and female — received training, as well as paid work.

The process confronted traditional cultural beliefs, and women commented during the training that it was interesting to learn things about water resources that they had previously assumed only men needed to know. Encouragingly, after initial construction had been completed, both men and women agreed that there was no difference between men and women’s abilities to perform semi-skilled labor.

Based on the MUS project’s success in these communities, we are now working with partners to see how we can make the case to scale up into planning processes at the municipal level. MUS is not an alternative to potable water, but rather, a complimentary approach. It is still important to work with local government to integrate co-management approaches into water services planning.

Inga Jacobs-Mata, IWMI Country Representative – South Africa

Photo: E.L.S.K.E. Photography

In response to IWMI’s award-winning MUS projects in South Africa, the country’s Water Research Commission and IWMI took up a follow-up study on the institutionalization of community participation in water projects in South Africa’s local government planning and design processes.

Beyond South Africa, the MUS approach today has proven reliable in providing life-changing water access to rural communities in more than 22 countries — strengthening water security in a way that supports more diverse, resilient lives and livelihoods.

Looking forward, the MUS approach holds a great deal of untapped potential for bringing sustainable water access to rural areas, given that the model is widely transferrable to communities around the world. To that end, IWMI’s MUS implementation guidelines are aimed at a broad audience, including governments, NGOs, and rural villagers, and will help other villages capitalize on the projects’ successes. But beyond the reports, partnerships, debates, webinars, and policymaking, real change in ensuring more convenient water access will require the continued amplification of the voices of communities taking on MUS projects, and the recognition of the enduring value of community water tenure.