15 Ways Wetlands Are Vital for Cities, Food and People – A Photo Essay from Sri Lanka

"We cannot afford to lose one more inch."

-Nadeera Rajapakse Rubaroe, Wetlands Ecologist and Consultant for the World Bank

When we think of urban infrastructure, what probably comes to mind are roads, pipes, drains and construction. But healthy urban wetlands are equally essential to developing livable cities.

Balancing green and grey infrastructure

The average citizen of Colombo passes over waterways and wetlands with likely very little thought for where water is coming from or going to. The canals of Colombo are connected to a system of lakes and wetlands that weave through the city.

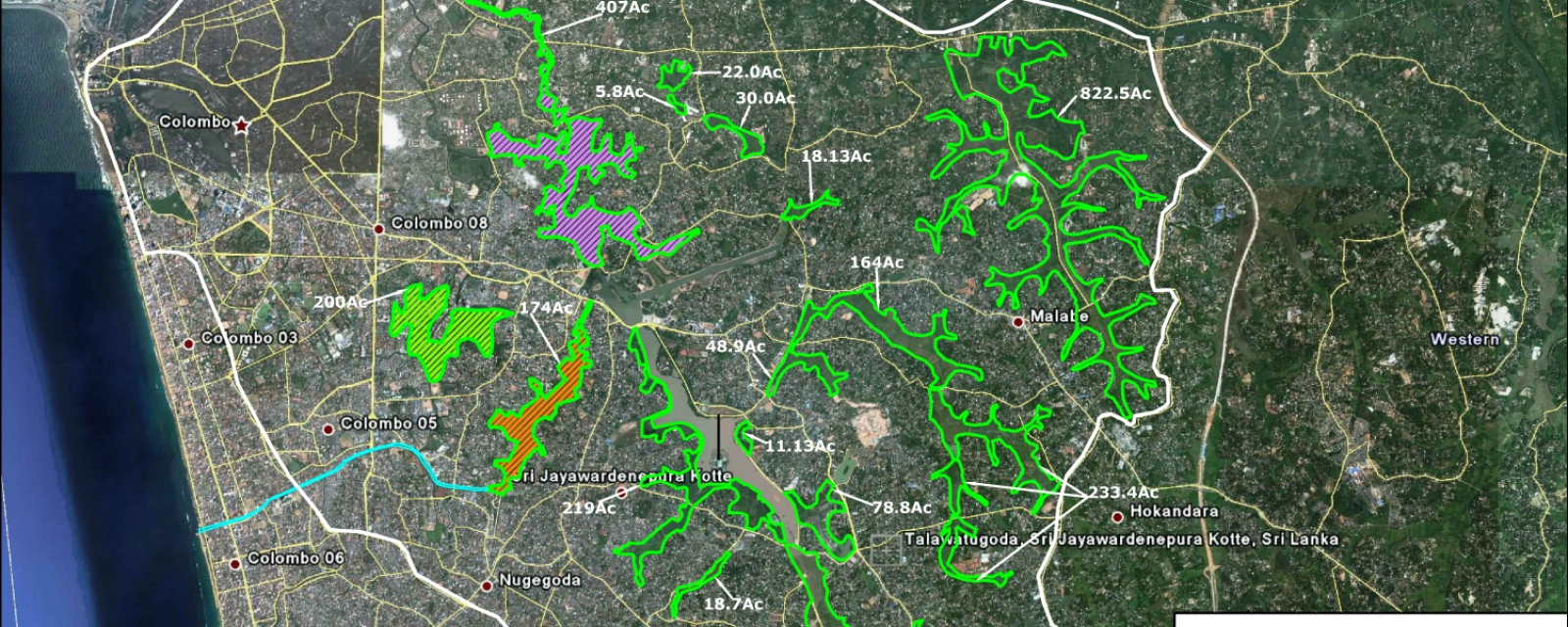

In fact, it’s bigger than most people realize: this unique wetland complex has a total estimated area of over 56,000 acres in the quickly growing Sri Lankan capital. A current hot topic of political debate, the government is juggling the needs of different sectors while deciding how to manage a quickly developing city, where dependable infrastructure is becoming a dire need.

Viewed through the sites and experiences in Colombo, here are 15 facts and photos showing the importance of wetlands.

The Colombo Wetland Complex

Whether or not people realize it, we all benefit from having wetlands in our cities. All too often wetlands are seen as unused or wasted space when in reality, they are extremely valuable elements of urban infrastructure whose benefits are vast, sustainable and cost-effective.

THE BENEFITS OF URBAN WETLANDS

Flood Mitigation

The wetlands of Colombo have enough storage capacity to fill 27,000 Olympic-size swimming pools with rainwater, making them extremely valuable for buffering floods. These marshy lands and plants absorb water and release it slowly, helping to regulate water levels while its plants and soils act as filters to improve water quality.

Temperature Reduction and Better Air Quality

Through the process of evaporative cooling, more than half of Colombo’s wetlands help to reduce extreme air temperatures. Furthermore, the plants and soils of wetlands capture and store airborne toxins, in turn helping to curb environmental health and pollution dangers.

_0/index.jpg?itok=vJLt391E)

Biodiversity

Wetlands can be urban biodiversity hotspots, home to over 280 species of animals and 250 species of plants in Colombo alone. The Talangama tank, one of the city’s healthiest wetlands, is home to over 100 species of animals in just 35 acres. Recreationists can see otters, fishing cats, monitor lizards, purple-faced monkeys on a walk around the lake.

URBAN FARMING

Local Food Supply

Ninety percent of the wetlands in Colombo are urban farms, and contribute to food supply in the city through the production of rice, vegetables, dairy and poultry products as well as through fishing and gathering of native plants.

Rural Livelihoods

Aside from food production, wetlands are an oasis of rural lifestyle. People depend on the health of the ecosystems to provide water for their livestock, irrigate subsistence gardens, harvest water lilies for sale, do their domestic washing and more.Wetlands are also an important source of traditional medicine.

Recreation

Recreation is a major factor in valuing wetlands. Peoples’ psychological quality of life and well-being is largely connected to access to recreation and exercise. Public parks allow all economic classes to enjoy open air and green space.

THREATS TO WETLANDS

Current Rate of Loss: 1.2% Per Year

And since the 1980s, as much as 60% of Colombo’s wetland area has been lost. The overall rate of loss of Colombo’s wetlands is about 1.2% per year due to indiscriminate filling and dumping of solid waste.

“Unless this trend is reversed, the wetland area will decline by one-third over the next two decades.”

– Dr. Priyanie Amerasinghe, Senior Researcher in Human and Environmental Health International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and its Water Land and Ecosystems (WLE) program

Poor water quality

The water quality situation in Colombo has become critical in the last 5 years. Throughout most of the city, water quality has been classified as “poor” to “extremely poor,” mostly because of untreated domestic wastewater.

Furthermore, dredging wetlands has been a highly controversial issue because it disrupts farming, the natural ecosystem processes and flows, and creates an environment suitable for invasive species to overtake native plants.

Invasive species

Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) is a very common invasive plant that is well established. Invasive species like this and other algae forms a mat over the water surface, reducing oxygen availability in the water. When it compacts and dies, it dries up seasonal water bodies, offsetting the normal life cycle of the ecosystem.

Citizen Action

Some communities in Colombo have taken it upon themselves to restore and clean wetlands of solid waste. The Talangama Wetlands Watch cleans every week with local volunteers and discourages illegal dumping in the area. Additionally, there are major issues of invasive algal blooms downstream from farms, and cleaning the water of algae is labor-intensive and expensive.

Whats next for the Colombo Wetlands

Groups like the Sri Lanka Land Reclamation &Western Development (SLLR&DC) in the Sri Lankan government are actively promoting the economic and livelihood value of the wetland system in Colombo. At present, a management strategy is being discussed, aimed at helping stem the loss of wetlands to urbanization. One of the biggest challenges around managing these urban systems is finding a balance where wetland conservation is made compatible with urban development.

The recent management strategy draws on extensive studies of the ecology, socioeconomic surroundings, and hydrologic modeling, and emphasizes the key role of science in providing an evidence base for restoration of wetlands across the city.

Ramsar: International Recognition

In 1990, Sri Lanka became a member of The Ramsar Convention, a national treaty that provides the framework for national action for wetland conservation and wise use of their resources. Colombo is being considered by the Ramsar Convention’s new program for Wetland Cities. If it receives this accreditation, there is strong incentive for the government to place high priority on the conservation and raising public awareness of the importance of wetlands.

“Investing in wetland conservation does add substantial value to the urban economy and it avoids many costly losses and damages. Sri lanka is emerging as a real leader in calculating these figures of economic values of wetlands.”

-Lucy Emerton, Environment Management Group, SOAS University of London

Going Forward

The greatest challenge to wetland management is understanding that urban development doesn’t necessarily have to come at the hefty pricetag of wetland loss. Sustainable management Colombo’s wetlands is a relatively low-cost investment in long term infrastructure, and Colombo cannot afford to lose another inch.

Thrive blog is a space for independent thought and aims to stimulate discussion among sustainable agriculture researchers and the public. Blogs are facilitated by the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE) but reflect the opinions and information of the authors only and not necessarily those of WLE and its donors or partners. WLE and partners are supported by CGIAR Fund Donors, including: ACIAR, DFID, DGIS, SDC, and others.