Can reporting on climate change become a problem – hampering policy-making on sustainability and providing an alibi for the real environmental villains? I believe it can. A growing tendency in the media to frame every environmental problem as rooted in a changing climate is having the effect of depoliticizing the issue and excusing local actors.

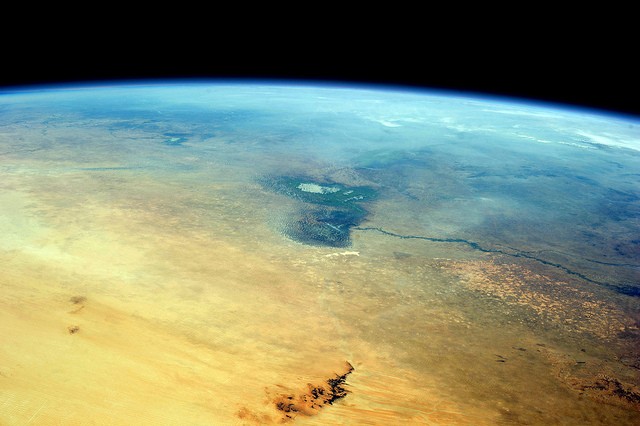

This has struck me forcibly while researching the worsening environmental degradation of wetlands in the Sahel – the Inner Niger delta, the Lake Chad basin, the Senegal river basin and others – and how this may be linked to growing insecurity and outward migration from the region.

The causes of migration are complex and wetland loss is only one element. But time and again, I was struck by something else: how the decline of wetlands is so often characterised in the media, as well as by politicians and even academics, as being caused by climate change. In truth, this is rarely the primary cause.

Misguided rationale

Usually the causes of emptying lakes, parched marshlands and shrinking deltas are much more specific and local. And blaming climate change becomes a recipe for not addressing those local causes. For example:

- Otherwise thoughtful and compassionate reporting from the Sahel by Western journalists often panders to the idea that climate change -- delivered by the energy profligacy of Western countries -- is the sole cause of environmental problems in poor nations. CNN recently headlined rural poverty in Senegal as “a regional symptom of a global problem: climate change”

- Growing law and order problems in such places give the story an extra dimension. According to Deutsche Welle, the story of the decline of Lake Chad, which straddles the borders of Nigeria, Niger, Chad and Cameroon and has incubated the rise of Boko Haram, shows that “climate change fosters terrorism”.

- And AFP recently highlighted the claims of Senegal’s President Macky Sall that “climate change brings conflict.” Sall told its reporter that “in the Sahel, terrorist groups are swarming… around Lake Chad and the Niger river, so we see the interaction between climate, security and terrorism. Everything is truly linked."

Yes, in the Sahel, growing security problems are often linked to water problems that wreck rural livelihoods such as fishing, pastoralism and recession farming shortages. But no, climate change is not -- yet at least -- the dominant cause.

Scratching the surface

In each of these three cases, real cause of the continuing decline of wetlands is predominantly hydroelectric dams and water abstractions for irrigation of cash crops like cotton and rice. And failing to acknowledge this can only hinder finding solutions to this dangerous new nexus of conflict. Meteorological evidence on the other hand, points out that rainfall, while not back at mid-20th century levels, has been on a generally upward trend for a couple of decades now -- since the mega-droughts of the 1970s and 1980s.

Sahel: As a result of river regulation by the Manantali dam in Mali, the Sengal River’s annual flood has been eliminated. An estimated 250,000 hectares of seasonally flooded land vital for pastures and recession agriculture has been lost. This has led to a “severe reduction in natural pasture areas” with “access to the river… very difficult for cattle,” resulting in “frequent conflicts between stockbreeders and farmers” along the river.

According to a recent assessment by the UN Environment Programme, Whatever CNN may imply, that has little to do with climate change.

Lake Chad: While climate change is routinely blamed for the lake’s decline which has shrivelled in recent years by as much as 95 per cent, causing mass migrations and social disruption, rains in the basin have been improving since 2002. The true reason for its demise lies in the fact that the rivers in Nigeria and Cameroon that once filled the lake have increasingly been tapped for irrigation projects. Likewise, water abstraction rather than faltering rains explains the recent shrinking of the Inner Niger delta in Mali.

This is not to say that the dams and irrigation projects serve no purpose, but that their downsides have been airbrushed from environmental history by short-sighted politicians seeking to defend their “development” projects. And reporters in search of simple stories about complex problems have too often been complicit in this.

Add new comment