Quantified at more than a million malaria cases each year

Large dams are a key contributor to economic growth, ensuring food security, alleviating poverty and resilience in the face of climate variability and change in sub-Saharan Africa. However, large dams frequently intensify malaria transmission – a mosquito-borne disease that globally kills approximately 627,000 people every year, mostly African children under the age of five.

In total, there are an estimated 174 million cases of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa annually. The disease also decreases productivity and increases the risk of poverty for the communities and countries affected. As a result, malaria causes economic losses in the region of over 12 billion US dollars (equivalent to 1.3% of total GDP) every year.

In Africa, the shores of many water reservoirs provide ideal breeding habitat for malaria transmitting mosquitoes. Many other water bodies in small dams, ponds and natural lakes and wetlands, also provide breeding habitat for mosquitoes.

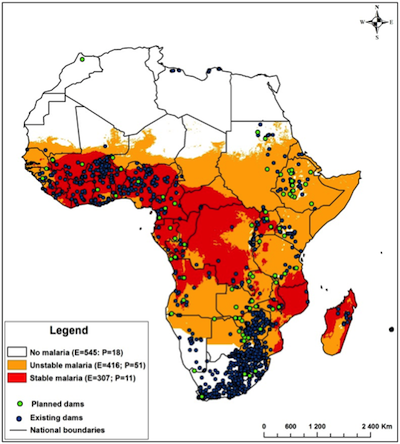

New research by a team from the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and the University of New England quantified the total malaria impact of large dams in sub-Saharan Africa. The locations of more than 1270 dams were mapped in relation to areas of stable (i.e. year-round) and unstable (i.e. seasonal) malaria transmission. The population at risk of malaria in these two epidemiological settings was estimated and the contribution of the dams to the malaria burden was determined. The impact of planned, not yet built, dams was also determined.

The research found that approximately 15 million people live within 5km of large dams and more than 1.1 million cases of malaria annually are associated with these dams. Current planned dams are likely to contribute an additional 56,000 cases annually. These numbers are conservative estimates because the locations of many more (perhaps 800) large dams in sub Saharan Africa are not recorded.

Who pays the price?

Current investment in large dams in sub-Saharan Africa is increasing to respond to the need for urgent economic development. Results of the present study call for intensive measures to mitigate malaria in the vicinity of the reservoirs created by existing and planned large dams. Whilst recognizing the importance of dams for economic development, it is unethical that people living close to them pay the price of that development through increased suffering and, in extreme cases, loss of life due to disease.

Water managers and development planners must invest in malaria control measures so that this adverse impact does not confound the larger aims that dams are built to achieve. Intensive malaria intervention efforts are particularly required in areas of unstable, less intense transmission where malaria impact of dams is the highest. Future investigation should look for additional cost-effective disease intervention tools such as reservoir management to help supplement the existing costly conventional malaria control measures.

There are many barriers to successful implementation of malaria control measures in the vicinity of large dams. A key question is how can dam builders and operators, be encouraged to work with relevant government agencies to mitigate the public health threats, not just malaria, that large dams pose?

Share you suggestions in the comments section below.

Download the publication (open access):

Malaria impact of large dams in sub-Saharan Africa: maps, estimates and predictions

/index.jpg?itok=EzuBHOXY&c=feafd7f5ab7d60c363652d23929d0aee)

Comments

We need to invest on disease control measures around water infrastructures. What has been missing was knowledge on how dams influence malaria in Africa. Such studies bring better understanding on the link between dams and malaria. I think dam engineers and water community as a whole has to work closely with health authorities in order to make sure that recommendations from Health Impact Assessments (HIAs) are properly implemented. I suggest that steering committee has to be formed at national-level that follows up implementation of HIAs while building dams.

How does the mechanism of breeding mosquitos work,why only in big dams and why in Africa,is it water is not clean. Is it the case in Asia,Australia,South America ,North america & Europe too

Mosquitoes do not commonly breed in the main waterbody of dam reservoir - mainly because of presence of numerous larval predators and unpleasant water waves and water depth for larval survival. Instead, they commonly breed in transient shoreline puddles formed alongside the reservoir shores. associated with dams.

Our study only focuses on large dams so it is difficult to comment on small dams (or microdams). However, previous studies have documented how puddles associated with long shorelines of small dams create favourable conditions for mosquito breeding.

Why in Africa? A number of factors attribute to the general high burden of malaria in Africa. Among them, the major explanatory factors are climate (hot climate facilitate development of mosquitoes and malaria parasites), intensity of vector control measures (limited resources for malaria interventions), health coverage (limited availability of health facilities and diagnosis and treatment facilities) and other socio-economic factors (e.g, poverty, quality of housing, etc ).

Does it spread near flowing water in rivers,in lakes between US and Canada.What kind of malaria prevention is suitable.

Most malaria mosquito species do not breed in fast-flowing water (i.e. rivers and streams) and lakes; they prefer still shallow water bodies. Weather is the major factor that limits malaria transmission. Mosquitoes and malaria parasites fail to complete their development in low temperatures (<16 C). That is why their global distribution is largely confined to the tropics.

Malaria prevention measures include bed nets, insecticide-impregnated curtains and mosquito repellents (e.g. buzz off ointment).

Sad to see this kind of comment from IWMI/WLE, in the absence of context.

The article reports 1 million cases of malaria associated with 15 million people (6.7% of the population, assuming one person, one case)

According to the WHO, the number of malaria infections in Africa in 2013 was 128 million (11.1% of the population)

So what this research seems to demonstrate is that living near large dams halves the rate of malaria infection.

You will find similar results if you look at the incidence of malaria in communities with permanent supplies of piped water. Yes, there are cases of malaria where there is piped water. But they will almost certainly be proportionately fewer than where there is no piped water (not least because cities are able to afford and institute vector control, not least because of the economic activity associated with piped water).

The rather obvious conclusion is that economic and social development reduce the incidence of malaria. Please put that as the headline to this blog, if only to maintain IWMI/WLE's reputation as a competent scientific institution! We certainly don't need IWMI to join the hysterical anti-infrastructure campaigns which will doubtless use this blog for their advocacy purposes.

Thanks for the feedback on our article. We agree with you that development and poverty alleviation contribute to malaria reduction. Indeed the development benefits of dams are recognized in our work. Nonetheless, there is ample evidence that dams built in malarious regions often result in increased malaria in the communities living in the vicinity of the reservoir. Our research confirmed this reality and, for the first time, determined a cumulative number of cases associated with large dams in sub-Saharan Africa. To be clear, the number of cases we quote (1.1 million) is not the total number of cases in the vicinity of dams; rather, it is the total number of cases around dams over and above those which would otherwise have occurred. In the paper, and indeed in this blog, we have been careful to put this in the context of the total number of cases annually in sub Saharan Africa (174 million) and also point out that, in addition to dams, there are many other anthropogenic activities (e.g. irrigation) that provide mosquito breeding habitat. We fully recognize the value of dams for socio-economic development. Nonetheless, we disagree with the assertion that if benefits outweigh costs, then costs should be overlooked. On the contrary, the greater the benefits that are derived from dams, the greater the reason to mitigate the adverse impacts.

In Africa, living in the vicinity of a reservoir increases the risk of contracting malaria roughly fourfold, Solomon Kibret and his co-researchers have found. The authors are right to recommend that dam builders must include malaria control measures in their projects. In addition, the human and economic toll of increased malaria incidence needs to be included in the cost/benefit analysis of power projects. Access to electricity is an important ingredient of public health, and the best option to provide this service should be selected in full knowledge of all costs and benefits. I salute Solomon Kibret and his co-researchers for closing an important knowledge gap.

Good article. Now it is time to think critically to address malaria issues associated with large dams in Africa. World Bank and other funding agencies should encourage dam builders to invest on malaria interventions. This is awakening call for Africa!