A review of “Can desalination and clean energy combined help to alleviate global water scarcity” by Aditya Sood and Vladimir Smakhtin in the Journal of the American Water Resources Association. The article is open access until September 2014.

With the world’s population barreling toward nine billion by mid-century, the planet’s fresh water resources are being strained as never before in human history. It perhaps comes as little surprise then that desalination — the process of removing salt from seawater to make it suitable for human use — is now a major global industry.

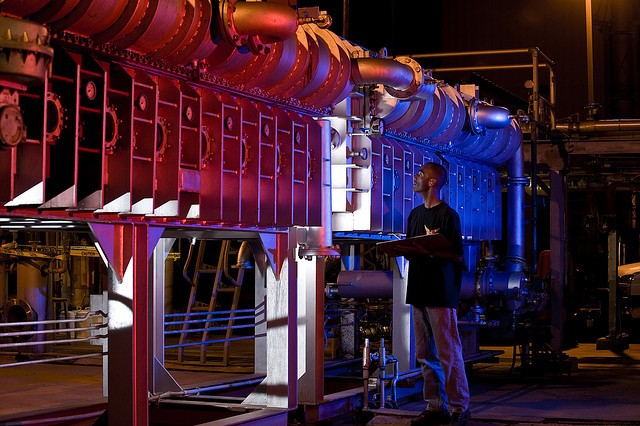

Flash desalination plant on Ascension Island, South Atlantic Ocean. Photo: U.S. Air Force photo/Lance Cheung

Flash desalination plant on Ascension Island, South Atlantic Ocean. Photo: U.S. Air Force photo/Lance CheungBetween 2010 and 2016, it is projected that nearly USD$88 billion in total capital investment will be channeled into the industry, as coastal nations around the world try to meet soaring demand for fresh water. But the technology’s potential for easing the global water crunch has been hamstrung by the fact that desalination requires huge amounts of energy, essentially making it unaffordable for most countries.

However, a potential game-changer for the desalination industry may be waiting in the wings. What if a virtually unlimited energy supply like the sun could be effectively combined with the planet’s virtually unlimited seawater supply to help ease global water scarcity issues? In their recently published paper, Aditya Sood and Vladimir Smakhtin of the International Water Management Institute add their respected voices to the growing chorus of researchers and experts asserting that using renewable energy to purify seawater could one day revolutionize desalination.

They concede that such technology may still be in its infancy. But the authors also shine the spotlight on long-term efficiency gains in both the solar power sector and desalination industry to make a convincing case that widespread deployment of renewable-powered desalination technology is not a matter of if, but when.

We live on a planet defined by water, but 97 percent of it sits in world’s oceans. Desalination today accounts for less than one percent of the overall global fresh water usage. However, as a coastal industry, it is extremely well positioned to reach a huge swath of humanity. Almost 2.4 billion people — or roughly one out of every three humans on the planet — live within 100 kilometers of an ocean coastline.

Greening the desalination industry

Desalination remains an energy-hungry industry relying almost entirely on fossil fuels. Consequently, only rich nations or countries with abundant and cheap domestic energy supplies have been able to effectively deploy the technology. To date, that list includes Saudi Arabia (the world leader in desalination by volume), the United Arab Emirates, the United States, Australia, Israel, and increasingly, China and India.

The authors suggest far more countries may be able to benefit from desalination if the industry is weaned off fossil fuels and instead powered by renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, or geothermal. Making this transition would drastically reduce the desalination industry’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Of all available renewable power options, the authors contend that solar (photovoltaic) technology has the greatest potential to become cost-effective and widely deployable enough to power desalination plants. Solar photovoltaic power’s worldwide installed electricity capacity rose by more than 40 percent every year during the first decade of the 21st century.

Furthermore, like seawater, solar energy is a virtually inexhaustible resource. The authors say ongoing efficiency gains in the solar sector dovetail nicely with the fact that desalination’s energy costs and overall operating expenses have dropped significantly in recent decades. However, desalinated water is still nowhere close to being cost-competitive with conventional water sources like rivers, lakes, or groundwater.

Widespread renewable-powered desalination can become a reality for 2050, argue the authors, based on their analysis of historical trends in the development of both the desalination and renewable energy sectors. This hypothesis, however, revolves heavily around the notion that solar power will become a “major source of energy in the future” — currently it produces less than one percent of the world’s energy – which means it needs to become cost competitive. (One potential means for this to happen would be if countries opted to invest heavily in solar power instead of hydroelectricity. After all, many new dams have a relatively limited lifespan of several decades — the same amount of time it may require solar energy to become cost competitive globally. Rather than construct more large dams that degrade fisheries and river ecosystems, why not place greater emphasis on developing solar energy to generate clean electricity for, among other things, pumping river water or groundwater?)

Challenges and limitations

Sood and Smakhtin acknowledge the inherent limitations of solar technology, admitting that even in a best-case scenario renewable-powered desalination could only meet domestic and industrial water needs, as opposed to meeting the larger water demands of agriculture. Also, due to the huge energy costs associated with transporting water, renewable-powered desalination could realistically help enhance water security only within 100 kilometers of the ocean.

Sood and Smakhtin briefly acknowledge desalination’s negative environmental impacts, and concede desalination may not be appropriate for all coastal countries. Meanwhile, other opponents of saltwater purification say the world should concentrate on conserving existing fresh water supplies, rather than rely on desalination to improve our water security by boosting supply.

Sood and Smakhtin’s ambitious prediction that one day “photovoltaic technology will be the dominant form of energy used in the desalination process” may also encounter some pushback from those who think this forecast relies too heavily on the idea that governments will be willing to provide the sizeable subsidies needed to advance the development of such technology. Further, many skeptics of solar-powered desalination are not convinced solar energy will ever prove reliable enough to provide a steady energy supply, given ongoing technological issues concerning solar energy storage.

The path to viability

Even in the face of these valid criticisms, solar-powered desalination is almost certain to become a commonplace sight in the century ahead. This is largely because the world’s hydrocarbon-powered desalination industry cannot be sustained indefinitely. As the world’s fossil fuels grow scarcer over time, they will become more expensive. Therefore, even if future technological breakthroughs make desalination less energy-intensive, desalination would still prove enormously costly because its price tag would be hitched to rising fossil fuel prices.

On the other hand, the solar power sector — once its current technological limits are overcome — can provide us a clean and essentially inexhaustible energy resource for desalination. Indeed, if we can fine-tune solar technology to the extent it becomes an affordable and reliable energy supply for desalination, the technology would hold enormous promise for populous, water-stressed coastal areas of the world. In North Africa and the Middle East, for example, the combination of water scarcity and ample sunshine could make the region an ideal testing ground. Perhaps hinting at what lies around the corner, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have both recently announced ambitious plans to build the world’s largest solar-powered desalination plants.

Solar-powered desalination may have a long road ahead before it becomes a fully functioning component of our global water supply network. But it is a road certainly worth exploring.

Comments

Solar power may not be the most economical for large scale water desalination for the moment. However the exciting thing is that small to medium size solar water desalination plant are already an economical solution in many places in the world:

https://sinovoltaics.com/technology/solar-water-desalination-decentralize...

A decentralized approach can be cost effective as you don't need to establish a complete 'water infrastructure' when unavailable.