Unlike transportation, medicine, communications, and even dam-building — all of which have experienced game-changing technological innovations during the past half century — canal irrigation has remained largely a technologically stagnant sector since the days of the Green Revolution, said Herve Plusquellec.

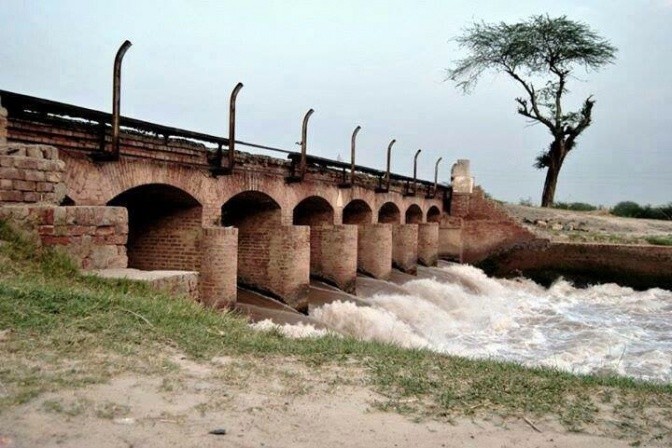

Aging canal infrastructure in Punjab, Pakistan.

Aging canal infrastructure in Punjab, Pakistan.Photo: Junaidrao on Flickr

Plusquellec, irrigation expert and formerly of the World Bank, was a keynote speaker at a meeting jointly convened by the Irrigation and Water Forum and UEA Water Security Research Centre on February 21. The meeting was held in London where irrigation experts from the World Bank, FAO and private sector discussed the prospects for large-scale surface irrigation to contribute to intensified agricultural production between now and 2050.

The effectiveness of surface irrigation in many countries in the early 21st century has been severely hamstrung, due to decades’ worth of poor infrastructure maintenance and inefficient operation. In a world that must produce more food than ever before on a finite supply of arable land in the decades ahead, the water-use inefficiencies of large-scale surface irrigation can no longer be tolerated. However, skepticism permeated the proceedings about whether governments and donor organizations have the political will or economic incentive to allocate the necessary funds to fix surface irrigation’s long-standing problems.

Surface irrigation’s importance to global food production cannot be overstated. Irrigated cropland produces some 40% of the world’s food. When canal systems are used correctly, they can enhance farmers’ access to water during different seasons, allow for several crops to be planted per year, and improve yields that boost rural incomes. (Indeed, crop yields from irrigated agriculture can be twice that of rainfed agriculture). For these reasons, modernizing surface irrigation needs to be a key component of any comprehensive strategies to make agriculture more sustainable and productive in the current century.

Aging infrastructure, mounting water losses

Some recent reports on sustainably boosting agricultural production have emphasized the role micro-scale irrigation can play. But they avoid discussion of the large-scale surface irrigation schemes entrenched across much of the developing world. Yet with the ubiquity of canal irrigation in key agricultural producers like China and India, canal modernization must be embraced alongside micro-scale technology as part of any broad-based approach to meaningfully bolster global food security.

One of the main challenges facing large-scale irrigation schemes is infrastructure maintenance, which has been routinely ignored for decades in many countries. After all, why invest in the rehabilitation of canals when we have enough water to absorb the inefficiencies?

The answer — and inconvenient truth — is that now in many countries, there is no longer enough water to absorb the inefficiencies. This is owed in part to the overpumping of groundwater spurred by subsidies that support food production and to changes in rainfall patterns induced by climate change.

Consequently, for many governments, the cost of inaction in rehabilitating or upgrading canal infrastructure may prove far higher in the long run than the cost of action. Especially as countries grappling with population growth and mounting food demand watch their water and food security erode with each passing year.

“Let’s speak out loudly now,” said Plusquellec, on the pressing need for greater investment in maintaining and modernizing surface irrigation infrastructure to improve water-use efficiency and support more sustainable food production.

The human side of the equation

Canal irrigation modernization is not just a question of infrastructure, however. Beau Freeman with Lahmeyer International argued that lack of operational experience among staff running large-scale surface irrigation systems is rampant in many developing nations, weakening the efficiency of canal irrigation due to poor data collection and ineffective management of the systems.

Governments and donor organizations too often do not give operational training for canal systems the attention or funding it deserves. Failing to invest in personnel training adequately is like handing someone the keys to a car but not teaching them anything about driving or maintenance; sure, you might get some mileage out of the car, but not nearly as much as you could have if someone had offered you a driver training course. Managerial know-how is key to running surface irrigation systems in an effective, sustainable manner that maximizes canals’ economic productivity.

Speakers briefly entertained the idea of a greater private sector role in managing surface irrigation schemes — as has been experimented with in Bangladesh — but their general consensus was that the key to improved canal oversight and operation lies in enhanced training for in-country engineers and managers.

According to Martin Donaldson, one country that has sought to maximize the productive potential of its irrigation works in this regard has been Vietnam, which has made agricultural modernization a top government priority since 2001 and invested in the professional development of project managers, systems operators, and contractors. Still, such examples of intensive managerial training for canal operations largely remain the exception, rather than the rule.

The urgency of now

With some projections showing that up to 60% more food will be needed to feed the world by 2050, perpetual inefficiencies in surface irrigation operations and management must be tackled now to avoid regional or larger-scale food crises in the years ahead.

The canal irrigation sector is simply too large and in too dire a state of disrepair to continue ‘business as usual.’ The proliferation of drip irrigation and other micro-scale irrigation will be helpful in bolstering water productivity and food security. But any comprehensive solution to sustainably intensifying global agricultural production must include surface irrigation modernization and funding commitments from governments and donors to give those reforms teeth.

“It is true that the tide of the battle against hunger has changed for the better during the past three years,” remarked Norman Borlaug during his 1970 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, referencing the late Green Revolution years. “But tides have a way of flowing and then ebbing again. We may be at high tide now, but ebb tide could soon set in if we become complacent and relax our efforts.”

Governments and donor organizations seeking to support sustainable agriculture today should heed Borlaug’s words, and stop exhibiting the complacency he warned of: Rather than kick the bucket down the road and make long-standing surface irrigation problems the burden of the coming generation, they should swallow hard and show the political and financial backbone needed to mitigate these problems before they become even more acute. Canal modernization is a continuous, long-term undertaking. Despite the present challenges, it isn’t too late to jumpstart the process.

Comments

Russell – while issues you raise may be true, like there is certainly a need for improved training in this sector, there are issues much larger than infrastructure and training needs. Was there any discussion in this conference on how social, political or agricultural systems have changed since the time the irrigation infrastructure was built? Instead of simply calling for an upgrade of irrigation infrastructure, we have to evaluate the changes in the systems for which the infrastructure was originally built. At least, it seems that the conference ignored that water control is not only technical, but in the past and still present, was achieved by controlling agricultural production and land ownership through the political system as well as the irrigation bureaucracy. Instead of simply promoting infrastructure upgrade and training of the irrigation bureaucracy we have to address the larger picture.

Dear Kai, thank you for your response. I wholeheartedly agree with the point you raise about the need for greater examination of the social and political contexts surrounding canal operations and modernization. The primary focus of last month's London event was on the technical aspects of deteriorating surface irrigation systems. Speakers placed far less emphasis on how social, political, and agricultural systems have changed since the introduction of canal infrastructure in many of the case study countries. They did wrestle with this topic a bit, but there was a general sense of pessimism in the room about whether entrenched political and bureaucratic systems could be meaningfully reformed to induce more efficient water usage in surface irrigation.

That said, there were a few comments made in passing suggesting that institutional modernization needs to happen in concert with technical upgrades and enhanced managerial training in order for surface irrigation systems to become truly sustainable from a water-use efficiency standpoint. Realities on the ground concerning political power structures, irrigation bureaucracies, and long-standing land-ownership arrangements certainly complicate the process of surface irrigation modernization, but these realities --- and gradual shifts in these realities that have taken place over the decades --- must be taken into account, as you say. Training and physical rehabilitation are important tools for more efficient water use, but there is no one-size-fits-all approach to modernization. Another interesting facet of canal modernization that needs to evaluated on a case-by-case basis concerns the role of water-user associations (WUAs). Out of curiosity, in your experience in the field, how effective have WUAs been in challenging the traditional power hierarchies that govern agricultural water use?

The main message of my presentation was on the coming stagnation of areas equipped for irrigation following the rapid expansion through over tapping groundwater during the last 2- 3 decades. To meet the demand for food by 2030 or 2050, performance of irrigation systems would have to improve over the present performance which is far below the level expected at feasibility level for both new and rehabilitation projects.

After that alerting introduction the presentation continued on the improvements of the physical infrastructure, as this was a subject of interest to the audience from UK ICID. However the speaker did not ignore the importance of social and policy reforms . One of the concluding slides was it is only the combinaison of physical improvements and institutional and policy reforms that the project objectives can be achieved. Many donor-supported projects have addressed only one side of the problem - and in most cases the software side only.